In most respects, the years have passed very lightly over Don Robinson. He remains vigorous and full of verve. But the one thing he really hasn't clung onto is the hair he wore as a teenager in the 1970s, when shaking the Bluegrass from his feet and embracing an alternative lifestyle in Northern California.

“Oh man, the hair,” he says. “Depending who you talk to, it just gets longer every time. It really wasn't that long. Probably over my collar. But they love to tell the story that it was waist length or beyond.”

His strong, chiseled features crease into one of those huge Don Robinson smiles, which you'll know very well if you're among his many friends in Kentucky. We're sitting in the kitchen at Winter Quarter Farm–just about as anomalous a name as you could find, for a place so irradiated by this human sunbeam. Nor is there any quarter given, in terms of his unstinting devotion to the horses grazing here, who have ranged from Zenyatta herself to the granddam of Kelso.

Harking back to his youth, however, Robinson admits that he was happy to be half a world away. Out in Humboldt County he had a young bride, a young son, and was hand-milking four cows.

“Just 'back to the land' stuff,” he recalls. “My grandmother had left me some stock. With the proceeds I bought a lovely, south-west face hillside and I built a house, built a barn, we grew food, grew hair, did the whole thing. Had some great neighbors, some that I still keep up with. It was really neat.”

But then, in 1977, came the awful summons home. Dad had Lou Gehrig's Disease. It was time to rally round, see if Robinson could piece back together the horsemanship he'd learned as a kid. Truth be told, he was already restless. He sensed an urban contamination seeping into their idyll–Eden was on its way to becoming a weed plantation–while their own, bucolic lifestyle would soon have been consumed by industrialization of dairy farming.

“Anyway Dad had been diagnosed, and everything was just falling apart,” Robinson recalls. “Even as it was, there wasn't much business here. Cattle, tobacco, a core of clients and horses. I don't think Dad owned any horses at all, at that time. His passion was training. He'd kept a barn at Keeneland for years. He loved to background horses, year round, pre-training. The nomadic trainer's life was not for him, he wanted to sleep in his own bed every night. So this place was perfect: he loved the farm, and the barn was 10 minutes away. It was a great life.”

Sadly his father could hold out only until 1980. On his own, Robinson felt like an impostor. He remembers coming clean to Jimmy Conway–Hall of Famer James P. Conway, “a great man”–after their mutual client Geoffrey C. Hughes indicated that he would be sending horses to Winter Quarter.

“Mr. Conway, I've got to tell you, I don't know a thing. Really I don't.”

He'll never forget the response.

“Donnie, you are a worker,” Conway said. “You'll be fine. You've got the right ethic. Don't worry about any of that other stuff, it'll come to you.”

And it did, Robinson concedes now. Not that the sweat of his brow was adequate on its own. His father had an expression about people who could work, only without ever getting on a wavelength with horses.

“That old boy,” he'd say, “could sleep with a horse and still wouldn't understand.”

“Either you have it naturally or you don't,” Robinson reflects. “And I've always just been able to connect with an animal. Just organically. I didn't have any teaching, any schooling. As a kid I'd hang out in the barn with the grooms. The more I look back, just the demeanor of those old timers was so impactful, the way they related to the horses. Back then it wasn't just a job. They lived with those horses. They were older men and you'd only call the veterinarian if a horse was dying. The grooms and trainers could do the rest: blistering, soundness, everything. If you had a pneumonia, I'd hear stories of them piling on newspapers and a blanket to sweat the horse.”

Those remedies go back centuries. No less timeless, however, was the loyalty of the farm's patrons, who gradually drew out an inborn vocation in Robinson.

“I mean, just think about those two,” he says of Conway and Hughes. “Both real characters, and both real mentors to me. Geoffrey was British, he'd inherited a shipping company, he lived by himself in Utah, skiing. He would hotwalk his own horses at Saratoga. And Jim Conway, he had been real tight with my father. So the reason I survived, when I came back from California, is because those two adopted me: the son of a New York beat cop, and this fascinating English gentleman, this man of the world.”

It feels like we're doing Robinson a disservice to dwell on those distant days, when the here-and-now remains so full of vitality. It was fully 42 years after his return, after all, that the Winter Quarter consignment broke the record for the New York Sale in Saratoga with a $775,000 Malibu Moon filly; and within the month scored the top two prices of a Book 2 session at Keeneland, at $1 million and $650,000. (This latter turned into Rock Your World (Candy Ride {Arg}), now standing at Spendthrift after becoming Winter Quarter's second graduate–emulating Midnight Interlude (War Chant)–to win the GI Santa Anita Derby. Both were out of mares sent by cherished friend and longstanding client Ron McAnally.) Farm graduates to have succeeded Zenyatta include Audible (Into Mischief), who emulated the GI Florida Derby success of Vicar (Wild Again) 19 years previously. Earlier breakthroughs, meanwhile, had been made by two GI Arlington Million winners in four runnings, Golden Pheasant (Caro {Ire}) and Star of Cozzene (Cozzene).

But the fact remains that none of that could have happened unless Robinson survived the initial crash course.

“So those clients were all like my uncles,” Robinson says, further invoking the names of Charles and Eddie Theriot. “[Mrs. Charles] Theriot had a really nice Sir Ivor filly. I was just barely cutting my teeth, so she was advised to have Lee Eaton sell her. I was not hurt but I did think, 'Oh gosh, that'd have been nice.' And that fall, out of the blue, Eddie sent me a commission. I just couldn't believe it. Those relationships, they were just very, very personal.”

Besides, the real start of this whole story goes a lot farther back. It takes a long time just to get through the hallway at Winter Quarter, so compelling are the photographs recording the era of Duntreath Stable, owned by Robinson's grandmother Suzanne, Mrs. Silas B. Mason. These include the iconic image of the stretch duel for the 1933 Kentucky Derby, Head Play versus Broker's Tip with the jockeys practically hauling each other out of the saddle. (Head Play put things right in the Preakness.) There's also a photograph of Mrs. Mason with Samuel Riddle, giving a 20th birthday cake to Man o' War.

Winter Quarter Silks | Sue Finley

“Oh, she was a force!” Robinson says. “She loved the horses, and she loved entertaining. I was only a little kid but remember her very well. She was scary, because she was such a huge personality, but always very gracious and I loved visiting her.”

Her stable had to be dispersed after the death of her husband, but their son Burnett had by then inherited a passion for horses. He wanted to drop out of school and ride steeplechases, so Mrs. Mason sent him to James Cox Brady in New York, to have some sense drummed into him. Brady, either misreading or ignoring his brief, told the young man to follow his dream.

The war interrupted Burnett's turf career, but did at least yield a name for the Fayette County farm he bought in 1948: Winter Quarter had been a coastguard lightship off Virginia, where he rode mounted patrols securing the shore against the contingency, presumably fairly remote, of sabotage by German frogmen.

Robinson was born the same year. Granted the depth of his own pedigree–his father also resurfaced Keeneland, incidentally, and laid out the training track–he was honored to revive his grandmother's silks to campaign Cambodia (War Front), bred in partnership with Eric Kronfeld, to win four graded stakes between 2015 and 2018.

“That was fantastic,” Robinson reflects. “I'd had the whole page for clients, and ended up buying into the family which was durable as hell. I'd bred and raced the mother, and I'd got to War Front at $25,000. But when we did the screening X-rays on the yearling, my vet just said, 'You're done.' He's pretty blunt! I was crushed.

“But I don't think she had three lame days that spring, and we did a stem cell procedure at his suggestion. We broke her in the fall and she was a star from the beginning. We gave her time, she didn't really get going until she was four, but she ended up winning $860,000 and Grade I-placed. And of course she was one of our own. There's been no thrill like Zenyatta. But to breed a racehorse as good as that, when you'd had the mother and grandmother, that was incredibly rewarding.”

Cambodia's first foal, a Medaglia d'Oro colt sold for $575,000, is now in training with Zenyatta's trainer John Shirreffs, which brings many things full circle. Shirreffs, a near-contemporary, himself had his drifting years in the 1970s, and the pair forged a great bond during the rise of the champion bred by Kronfeld and raised at Winter Quarter.

Kronfeld had arrived at the farm fairly circuitously. It had initially seemed an ample boon, to Robinson, simply to receive some Marshall Jenney and George Strawbridge mares when King Ranch was sold.

“I don't do much seasonal stuff anymore,” Robinson says. “It was a lot of work. But these magnificent mares, when they came in, gave me chills. It was like when I first got some King Ranch yearlings to break: I'd been used to Chevrolets and Fords, and then these Ferraris come in. I said to Helen [Alexander] that she taught me what pedigree was all about, just by seeing that difference. They could be crooked-legged or anything, but they just had that fire.”

Jenney brought in Kronfeld, too–and when that pair fell out, the music executive declared that he would leave his couple of mares at Winter Quarter.

“Eric was gruff, and Marshall was gruff!” says Robinson, by way of humorous explanation. “Anyway one of Eric's mares was For The Flag (Forli {Arg}), the granddam of Zenyatta. Over time Eric and I became fast friends. We were night and day, but somehow a great match. He was the New York lawyer, so sharp, knew a lot of stuff I didn't. But I knew stuff he didn't know, too. He was a real curmudgeon, but I had a lot of affection for him. I still miss him.”

Zenyatta | Sarah Andrew

When they were selling Zenyatta, they argued over the reserve. Kronfeld got his way and David Ingordo was bewildered to get her for just $60,000. But then Robinson had opposed the Street Cry (Ire) cover, as too European, so nobody got everything right!

Here, then, is a man who has not only seen an awful lot over the years, but can entwine it with many rich strands of the past. And who can say what fresh chapters may yet be written by the couple of dozen mares on these 300 fertile acres?

Sure, our world has changed a lot over the last 75 years. Robinson remembers chatting with Bernie Sams at a sale, maybe 25 years ago now, and the Claiborne manager commenting: “You know what's changed, Donnie? These days, people would rather make $1 million in that ring than win a Grade I.”

“Believe me, I love to sell a horse,” Robinson says. “But boy, the reward is on the track. I mean, that's why we're doing this.”

Sure enough, this relatively small farm has consistently produced elite runners decade after decade.

“First of all, it's great ground,” Robinson says. “My father knew what he was doing. You can't raise them on a rock pile. I always say Kentuckians aren't very smart, but the smartest thing we do is take care of this land that we're lucky enough to be on.”

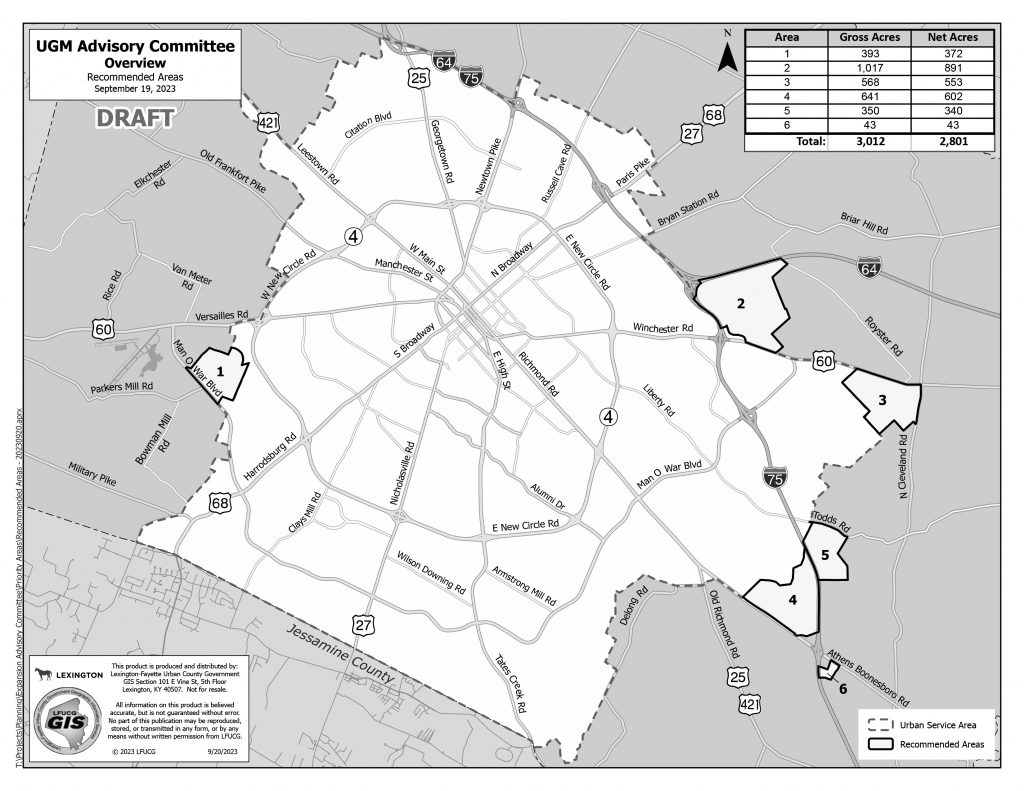

Robinson has certainly walked the walk, on that account, having long since gone in “with all four feet” on local land use policy. In fact, he started out by suing the planning commission–and ended up being asked to join it. Subsequently he was a founder of the Fayette Alliance, a local land use advocacy organization.

“Farm land's under threat, but it feels like we've got the community's ear,” he says. “In polling, what do people consistently value? The farms, the green space. They feel they own that. Now, you have to buy into that. It can't just be us guys behind the black fences, that won't work. But people get it: the rings of economic impact, what this business means to the state, and how this land really is a finite resource.”

With the parcel under his direct stewardship, however, Robinson is happy to play a rather shorter game: taking and enjoying each day as it comes.

“I'm still out getting horses every day of the week, all year, in all weather,” he says. “It's what I do, and it's what I love. I don't do nearly as much as I used to, thanks to great staff, but the hands-on is so important.”

He exudes such boyish enthusiasm, in fact, that you can still discern the teenager who used to go to Saratoga with Charlie Nuckols.

“I was about 14 or 15 and we worked the sale and really thought of ourselves as grown men,” he recalls. “And then Charlie, who was a little older, told me about riding the train to Santa Anita with horses. I said, 'You got to be kidding me.' Because I used to love to ride vans with horses. So I got myself introduced to Tex Sutton–another guy, thank God, that took me under his wing.

“So for the next couple of summers I got to take horses through Cincinnati, St. Louis, all the way to Santa Anita, on a baggage car. I could have done it the rest of my life. It was the most magnificent deal ever. The door was wide open and you're just sitting there watching the country pass by. And if a horse ran a temperature, you just let the conductor know–and at the next stop the vet would come and, though there were passenger cars too, that train did not move till that horse was treated and cleared, or else needed to be offloaded.”

That opens a still farther horizon of memory: his father and his farm manager, telling him about how horses would be led into the branch stations from outlying farms in Scott County, Georgetown, Jessamine County.

“Kids would be paid 50 cents to take them downtown, to load on the box car to Saratoga,” he recalls. “They'd start at dusk and lead them by lantern. There was a one urban streetcar to Georgetown. They had to wait till that stopped, because all the horses would freak out. But once the last car had gone through, then they'd walk the horses in and put them on the train at 2 a.m.”

No less a man than John Magnier, coming to Winter Quarter to appraise Zenyatta's dam, once congratulated his host: “Don, this is a magnificent place.”

“I knew that to be no idle compliment,” Robinson says proudly. “But here's the thing, my people all had patience. They had a program, and they stuck with it. To me, that's for all time. If you're not patient in this, you'll be a flash in the pan.”

And that still applies at his time of life, no less than when he was gazing at the continent unscrolling from a train car. That's why Robinson has decided not to sell Cambodia's yearling filly by Tapit.

“I'm an old man now, and I have a great partner in Allen Schubert,” he explains. “We were little kids together, and he loves to race one. I'm not sure I really have an exit strategy, anyway. Mostly, I don't want one. The life, this farm, this land: no kidding, I just got lucky that my father started a small horse business. It's been pretty remarkable. I've had a lot of good horses. I've worked really hard, but I've always had wonderful people. And that's key. Wonderful people I think can bring wonderful horses.”

The post Winter Quarter Remains Evergreen appeared first on TDN | Thoroughbred Daily News | Horse Racing News, Results and Video | Thoroughbred Breeding and Auctions.

Source of original post