By the time a stallion has established himself at stud, his fee is usually determined by performance, not the hype that surrounds new horses when they first enter stud. There are, of course, many ways to measure performance, including progeny earnings (which determines placement on the General Sires list), percent of black-type winners to named foals, quality of runners, number of Grade l winners, etc.

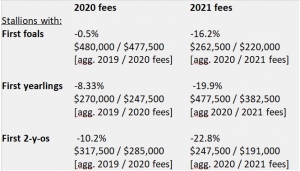

There are seven thoroughly proven stallions that will stand for $150,000 or more in North America in 2021, and these elite horses–Into Mischief ($225,000), Tapit ($185,000), Uncle Mo ($175,000), Curlin ($175,000), Medaglia d’Oro ($150,000), War Front ($150,000), and Quality Road ($150,000)–more than make the grade whichever way you slice and dice statistics. For instance, this select group sires black-type winners from named foals at rates of between 7% to 12% (see accompanying charts), which is the gold standard nowadays in the era of big books. [Note: Younger stallions will have lower percentages because their 2-year-old crops will be a larger percentage of the whole.]

Each year as the breeding season rolls around, a dwindling number of smaller owner-breeders frequently ask us at Werk Thoroughbred Consultants to recommend the best proven stallions standing for $15,000 or less. These people, who once made up a larger percentage of owners, need sires with track records, because they race what they breed and have no room for error. A shiny new horse at $15,000 is unproven and too much of a gamble for them, whereas that same first-year horse might well be the choice for a commercial breeder shopping in that price range. It just so happens, however, that the types of stallions best suited for small homebreeders are inexpensively priced these days, not because they lack performance but because they tend to be old and are mostly ignored by a large swath of folks who breed primarily to sell. And it’s the young stallions that sell.

Old stallions, like old people, tend to be underappreciated in a climate that rewards youth.

In fact, older proven stallions that aren’t elite are frequently priced lower than they should be if performance itself were the sole criteria for fee determination, but with them it’s not. They are simply not fashionable, even if they once were.

For those of you who breed to race, I’ve listed in another chart 10 favorite older stallions that will stand next year for $15,000 or less, and they were chosen primarily because they satisfy two criteria aside from my preferences for them: they are (or were last year) ranked on TDN‘s General Sires List; and they get a minimum of 5% black-type winners from named foals, which is a rate close enough to rub shoulders with some of the elite sires standing for $150,000 or more, but at a significantly lower fee that makes them both attractive and affordable for homebreeders. This group can get you a horse good enough to play with the big boys. There are a few others I could have included–my apologies–but didn’t for space considerations.

Here they are by descending stud fee; statistics are for the Northern Hemisphere:

Midnight Lute ($15,000) – This son of Real Quiet at Hill ‘n’ Dale is ranked #12 on the General Sires List, which puts him ahead of both War Front and Quality Road this year, and note also that he’s one of the younger horses in this group with nine crops of racing age. He gets 5% black-type winners from named foals and has demonstrated the ability to sire runners of the highest class, such as Eclipse Award winner Midnight Bisou, one of the best fillies of her generation. Altogether, he’s sired 33 black-type winners and four Grade l winners, including 2020 Gamely S. winner Keeper Ofthe Stars.

Lemon Drop Kid ($15,000) – Through 17 crops of racing age, this well-bred son of Kingmambo has sired 7% black-type winners from foals, the same as his mate Quality Road at Lane’s End. Lifetime, he has 96 black-type winners, including nine Grade l winners, and he’s ranked #44 on the General Sires List this year with such horses as Canadian classic winner Belichick, Glll Ontario Derby winner Field Pass, and 7-year-old French Group 2 winner Red Verdon. In Japan, he’s represented by Godolphin-owned 2-year-old Lemon Pop, who won a non-black-type Kentucky Derby points race on Nov. 28 at Tokyo after winning his debut before that. Though he gets top-level turf and all-weather runners, his daughter Lemons Forever won the Grade l Kentucky Oaks on dirt and has since become a Kentucky Broodmare of the Year.

Mineshaft ($15,000) – A sire of 51 black-type winners through 14 crops–six at Grade l level, including $3.3 million earner Effinex and successful Darby Dan sire Dialed In–he stands at Lane’s End alongside Lemon Drop Kid and is a son of A.P. Indy. He’s at #55 on the General Sires List and is represented this year by Glll Canadian Derby winner Real Grace in what for him is a slow year. He gets 5% black-type winners from foals.

Sky Mesa ($12,500) – This son of Pulpit has sired 73 black-type winners and four Grade l winners through 14 crops, and it’s notable that he’s also the sire of three Canadian champions that aren’t on his list of Grade l winners. Last year, his 2-year-old daughter Perfect Alibi won the Gl Spinaway S., and this year he’s represented by two 3-year-old black-type winners, both of them graded placed. He gets 7% black-type winners from foals, is ranked #66 on the General Sires List, and stands at Three Chimneys.

Stormy Atlantic ($10,000) – The elder statesman of this group, he’s a son of Storm Cat at Hill ‘n’ Dale with 19 crops of racing age. Throughout his career, he’s maintained a 7% rate of black-type winners to foals and altogether has so far sired 103 black-type winners and seven Grade l winners (eight, if you count one in Argentina). His gelded son Stormy Liberal won the Gl Breeders’ Cup Turf Sprint twice and was an Eclipse Award-winning turf male, while in Canada he’s had three champion juveniles and Horse of the Year Up With the Birds, also a Grade l winner in the U.S. Among his top performers this year are Grade ll winner Big Runnuer, a 5-year-old; Grade lll winner Neptune’s Storm, a 4-year-old who won a Grade ll race last year; and 7-year-old Stormy Antarctic, a previous Group 2 winner who was second in the G1 Prix d’Ispahan in France in July. Though he’s unranked on the General Sires List in 2020 (he was ranked last year), he consistently gets sound and durable runners with a high degree of class.

Midshipman ($7,500) – This son of Unbridled’s Song at Darley is the youngest horse here with only seven crops of racing age – the same as Quality Road. He’s #47 on the General Sires List and to date is represented by 28 black-type winners in the Northern Hemisphere, a rate of 6% to foals. Though he doesn’t have a NH Grade l winner yet, he has three in Brazil, one of which, Royal Ship (Brz), is Grade ll-placed in California this year. His leading earner to date is Grade lll winner and Grade l-placed Lady Shipman ($902,387), whose son Golden Pal won the Gll Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Turf Sprint this year.

Mizzen Mast ($7,500) – Based at Juddmonte, this son of Cozzene has eight Grade l winners to his credit (nine, if you include another in Peru) from 60 black-type winners, for a rate of 6% black-type winners from foals. One, Flotilla, is a Gl Breeders’ Cup Juvenile Fillies Turf winner and a French classic winner, taking the G1 Poule d’Essai des Pouliches at three. Another, Full Mast, is a Group 1 winner at two in France, while Sea Defence (also known as Giant Treasure) won a Group 1 at five in Hong Kong. His best-known runner, the mare Mizdirection, twice won the Gl Breeders’ Cup Turf Sprint, and in California he’s had the winners of such races as the Gl Hollywood Derby at 10 furlongs on turf; the Gl Charles Whittingham Memorial at 10 furlongs on turf; and the Gl Hollywood Gold Cup at 10 furlongs on all-weather, among other prestigious races. Yes, he’s a turf sire with his best runners, but note that his daughter Sailor’s Valentine won the Gl Ashland S. at Keeneland on dirt. He’s #74 on the General Sires List.

Silent Name (Jpn) (C$7,500) – This son of Sunday Silence stands in Canada at Adena Springs and is represented by 27 black-type winners, or 7% from foals, and he’s #83 on the General Sires List. He doesn’t have a Grade l winner yet in the Northern Hemisphere (he has one in Brazil), but his graded winners include several who have placed at the highest level, including Grade ll winners Silentio and Fanticola, plus listed winner Mr. Online. His current runners are headed by Grade ll winner Silent Poet, a 5-year-old.

Freud ($6,500) – A Storm Cat brother to Giant’s Causeway, he’s a New York-based sire at Sequel with enough proven form nationally to take him out of the regional ranks, though he’s a must-use sire for the lucrative restricted program in New York. The sire of 55 black-type winners and four Grade l winners (plus an additional three in Argentina) through 16 crops, he gets 6% black-type winners from foals. His best include Gl Cigar Mile H. winner Sharp Azteca, now at stud at Three Chimneys. Freud isn’t ranked on the General Sires List this year, but he was last year.

Include ($5,000) – This son of Broad Brush at Airdrie is responsible for 45 black-type winners through 15 crops, including five Grade l winners (plus another five bred in Argentina), and he’s ranked #98 on the General Sires List. He gets 6% black-type winners to foals and has a notable bias for fillies: all five of his top-level winners are fillies, headed by millionaire Panty Raid. If you included his five Group 1 winners from Argentina, nine of the 10 are fillies. His top current runner, 3-year-old Grade ll winner Sconsin, also is a filly, but he does have champion Canadian juvenile colt Riker and Grade lll winner and Grade l-placed All Included among a smaller group of accomplished males.

Sid Fernando is president and CEO of Werk Thoroughbred Consultants, Inc., originator of the Werk Nick Rating and eNicks.

The post Taking Stock: Performance vs. Stud Fee for the Small Owner-Breeder appeared first on TDN | Thoroughbred Daily News | Horse Racing News, Results and Video | Thoroughbred Breeding and Auctions.