In Fair Hill, Md., the recent site of a large international equestrian event, several farriers gathered, not necessarily an unusual occurrence where events that involve horses are concerned. However, this day lacked the usual sights and sounds that horse people have become accustomed to when considering farriers: no ringing anvils, no screeching grinders or sounds of clinches being blocked. The assembled farriers did not unpack toolboxes from their rigs or unload any horseshoes; nonetheless, the group descended upon the Fair Hill show grounds only armed with cameras, measuring devices, laptops, sensors, and a desire to push their skill into the 21st century. A nearby sign encouraging participation in the study simply read, “Farriery and Gait Assessment…Free Analysis!” The pot was sweetened for the skeptical, reluctant, and resistant, with a $1,000 raffle for participants, including other inducements donated by Dover Saddlery and the American Farriers Journal.

The gathering of farriers moonlighting as researchers and data collectors turned out to be a mini reunion of sorts, with the majority being recent graduates of the Royal Veterinary College's (RVC) Equine Locomotor Research (ELR) program, some traveling great distances to attend. Overheard conversations included a recount of the last resident weekend for the course (hosted in February 2020) on the eve of some new coronavirus outbreak elsewhere on the globe and the resulting effects on travel, while another member of the group was heard expressing their disappointment with failed attempts to encourage some rider/horse combinations participation, attributing resistance to cynicism or a possible jog mishap on the eve of a major competition.

In attendance, farrier Doug Anderson of Mount Airy, Md., informed onlookers and potential partakers that in the field of hoof-related research, which includes approximately 159 studies examining the hoof and shoeing, only five were authored by farriers. He explained that the RVC's ELR program was created with the goal of providing the tools and knowledge to facilitate changing this narrative.

The Fair Hill study, the brainchild of Pat Reilly, another RVC graduate and Chief of Farrier Services at University of Pennsylvania's New Bolton Center since 2006, explores potential correlations of symmetry and performance using a sensor-based gait analysis (EquiGait). The New England native, who has a life-long family connection to horses and their business which retrained off-track Thoroughbreds for eventing, segued into shoeing after a four- or five-day stint as an exercise rider and a trainer's recommendation to seek out another line of work. Explaining the origin of the U.S. version of the ELR Program, Reilly shared that his plans to attend the UK program were derailed by Brexit and visa restrictions, resulting in his lobbying hard the program's creators (Dr.'s Renate Weller and Thilo Pfau) to implement a satellite program in the U.S.

“All farriers have different ways to shoe, and in the absence of facts everyone has an opinion. [Farriers] don't have to prove it,” Reilly said, explain the need for improving farrier education and increasing evidence-based shoeing through research.

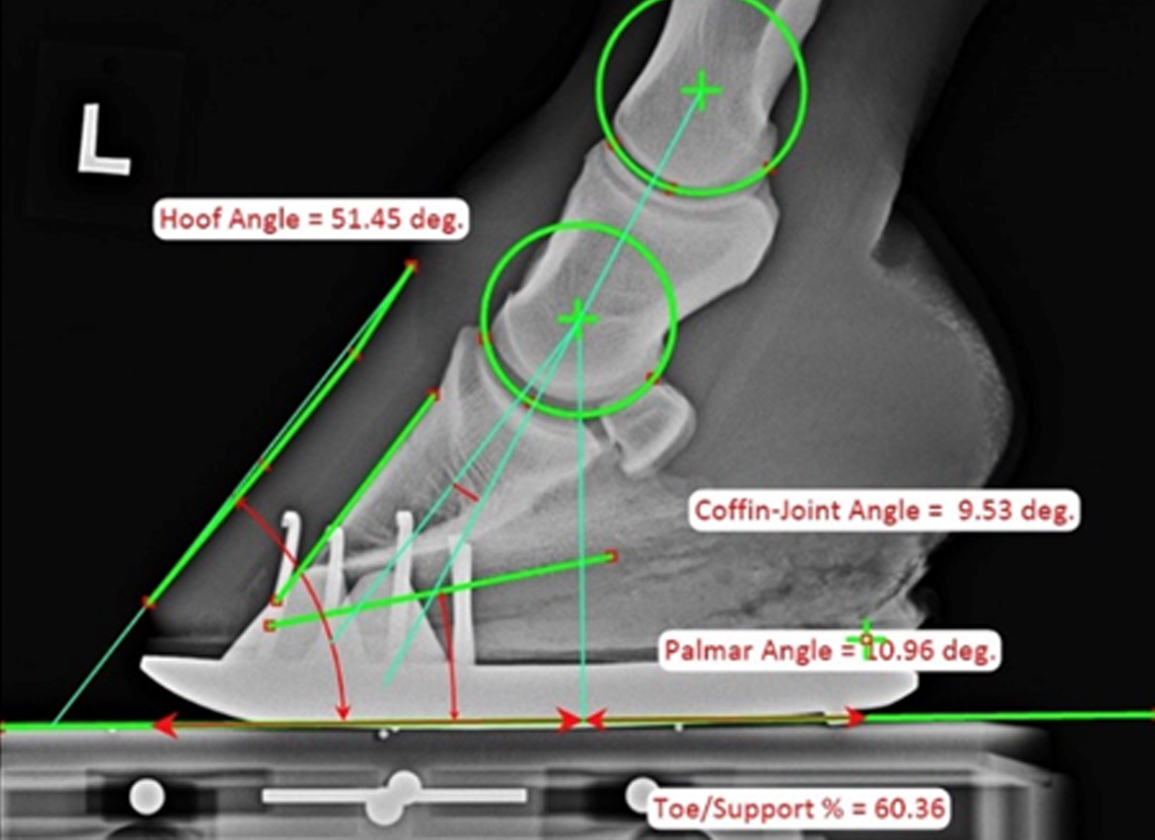

In choosing the Fair Hill venue to perform his study, Reilly explained that it offered a “good opportunity” to measure top performance horses, while seeking possible correlations of hoof morphologies, symmetry of movement, and any resulting effects on performance. Ensuing observations, images, and simple measurements were recorded (i.e.: hoof angles, toe lengths), as were the types of shoes, including any possible additional interventions (pads, glue-ons, pour-in materials).

The study's primary focuses are based on the results of measurements using the EquiGait system, an inertial measurement unit (IMU) sensor-based technology developed by Pfau. EquiGait is similar to existing devices commonly known as “lameness locators.” However, Pfau, who was recently appointed Professor to the University of Calgary's Departments of Veterinary Medicine and Kinesiology, explained his system goes one step further than the lameness locator, which uses sensors placed on the pole and sacrum to detect asymmetry. In comparison, EquiGait additionally incorporates the withers, offering the ability to pinpoint asymmetries occurring in front or behind. Pfau added that these systems' main characteristic seek to identify asymmetry of motion, a possible sign of lameness. Measurements of the upper body, movement, and the interaction between the sensors capture function of the legs, including weight bearing, pushing off, and indirect conclusions about force distribution between limbs.

When asked about the usefulness relating to Thoroughbred racing, Pfau referred to knowledge gained from studies and routine use of this technology by Dr. Bronte Forbes, previously based in Singapore and presently in Hong Kong. He noted Singapore's use of sensor technology as an objective assessment of lameness and confirmation after a veterinary check results in a visual detection. The technology's use has been widely accepted as a trusted veterinary tool. Pfau explained racing's biggest challenge is the reality of horses being pushed to their limits, and asymmetries connected to potential issues are never quite the same, with huge variations in measurements and data. However, both Pfau and Reilly believe using sensor technology in racing may quantify farrier interventions and its measured effect, while identifying existing asymmetries and quantifying why one may enhance performance and another may precipitate a breakdown. Additionally, they agree that farriers do play a huge role in affecting horse's movement and symmetry and the use of this type of technology can only be beneficial.

Pfau asserted, “Shoeing is the most powerful thing that we can do; it has huge consequences.” He underscores shoeing adjustments can be directly quantified, as well as having the potential to redistribute forces highlighted by ongoing examinations of upper-level dressage horses. The study investigates the effects of shoeing on multiple surfaces and attempts to distribute forces symmetrically which without intervention may have longer-term implications with negative ramifications. According to Pfau, for now, sensors are a great resource for veterinarians, assisting in the detection of potential causes of lameness and identifying an area of concern. He also believes the continued collection of data is necessary and imperative, as there is a likelihood that long-term goals will have future sensors used as a preventative measure with an ability of early detection.

Whatever the outcome of Reilly's study, Pfau adds, it's good the conversation continues, forcing the art of shoeing closer to the science of shoeing, and is a great start in providing more facts and fewer opinions. Reilly stressed that he was extremely proud that out of the 10 or 12 graduates, seven or eight took time out of their busy schedules to participate and assist. Of the 40,000 farriers in North America, there are presently 10 or 12 with research training.

“Imagine if we had 10,000 or 12,000, 1,000 or 1,200 even… We have an incredible ability to help our horses and become better at what we do by using evidence and changing how we teach,” said Reilly.

As a lifelong horseperson, rider, farrier, I am unsure of the logic–nor do I understand–the resistance or objections to exploring and unearthing potential issues with the use of noninvasive sensor technology, which objectively measures and assesses gait(s), perhaps detecting a need for an adjustment in shoeing and/or training. The resulting data could potentially enhance or improve performance or, more importantly, detect and derail a potentially catastrophic issue before it's too late.

At the end of the day, what do I know? I hold an inverted unnatural position for hours on end bending metal for a living.

Jude Florio, who has served as a professional farrier for over 20 years, earned a graduate diploma from the University of London's Royal Veterinary College in Applied Equine Locomotor Research. He is among the current MSc Equine Science cohorts studying at the University of Edinburgh, Royal 'Dick' School of Veterinary Studies (June 2023).

The post Detecting a Possible Future for Shoeing? appeared first on TDN | Thoroughbred Daily News | Horse Racing News, Results and Video | Thoroughbred Breeding and Auctions.