The relationship between trainer and assistant can often be tumultuous and fleeting, while in other instances, it can prove life-altering and enduring. And every once in a while, the spark ignites, paving the road to great glory and even the Hall of Fame.

When it was announced that trainer Todd Pletcher would be inducted into the National Museum of Racing's Hall of Fame this summer, most could not have been surprised that the 53-year-old would have been granted the honor in his very first year of eligibility. In truth, there was never really any doubt that it would happen so quickly. Having accomplished more in the last two decades than most trainers will achieve in their lifetimes, the Dallas, Texas native towers over his competition with $406 million in career earnings. In fact, he leads his nearest pursuer, fellow Hall of Famer Steve Asmussen, by a tick over $50 million even though his counterpart has started twice as many runners. Pletcher's resume is commanding: Seven Eclipse Awards as the nation's outstanding trainer; 10 Eclipse Award winning champions, and five winners of Triple Crown races. Among the plehtora of equine athletes that have helped him place seventh overall with over 5,100 career victories are Rags to Riches, Ashado, Always Dreaming, English Channel, Honey Ryder, Palace Malice, Wait a While, Fleet Indian, Shanghai Bobby, Speightstown, Super Saver, Stopchargingmaria and Uncle Mo.

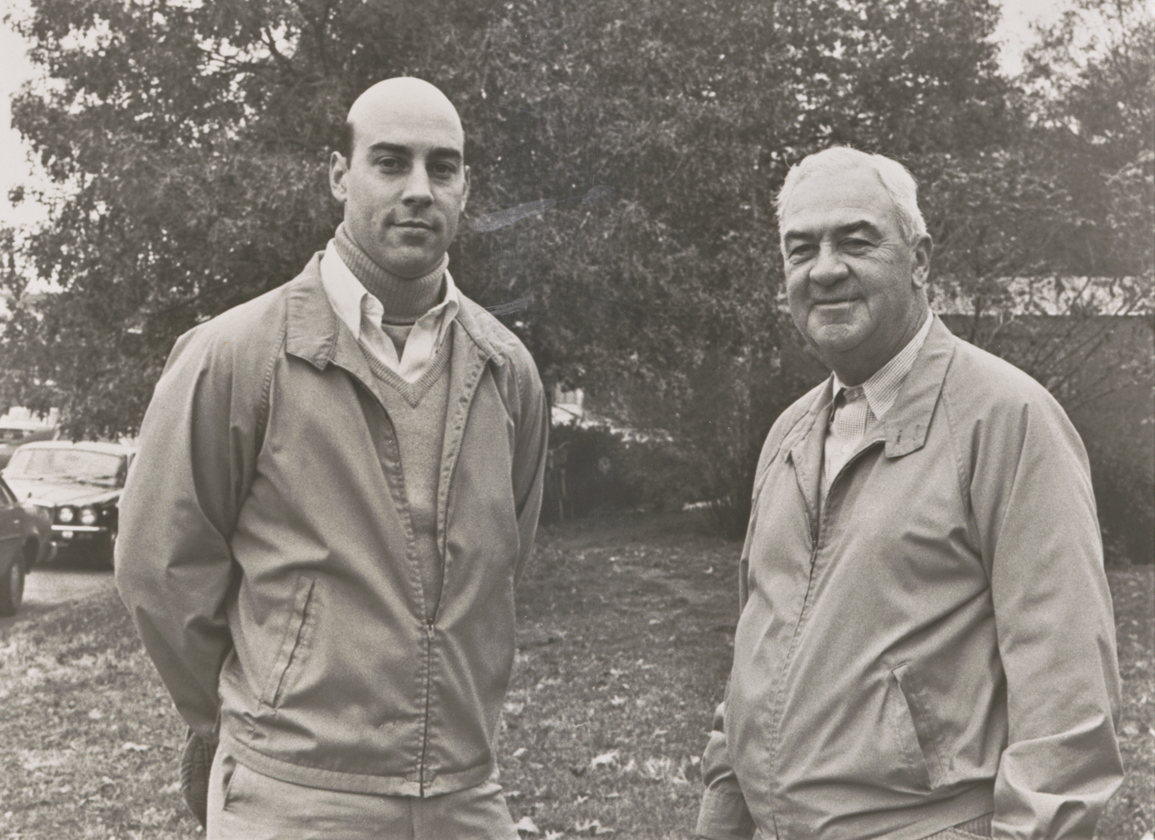

While there is no guarantee for success in racing, apprenticing under some of the game's biggest names certainly couldn't have hurt. Similarly to a formidable slew of equine champions and human proteges, Pletcher hails from the formidable program of D. Wayne Lukas, who was also inducted into the great hall in his first go around in 1999. While attending the University of Arizona, Pletcher served summer stints working as a groom for Lukas at Arlington Park between his sophomore and junior years before joining another Hall of Famer, Charlie Whittingham, between his junior and senior years.

Upon his graduation, Pletcher joined Lukas's New York string in May of 1989, initially serving as foreman before being promoted to assistant in 1991. Splitting his time between New York and Florida, he managed Lukas's powerful East Coast string through 1995, and in that time, helped develop a bevy of stalwarts, including Horse of the Year Criminal Type and champions Thunder Gulch, Tabasco Cat, Open Mind, Steinlen, Serena's Song and Flanders. Lukas is responsible for 14 Classic victories, 20 Breeders' Cup wins and has trained 26 divisional titles and a trio of Horse of the Year champions. The horseman was the first trainer to reach $100 million and later the $200-million mark in career earnings. A native Antigo, Wisconsin, Lukas was the leading North American trainer in earnings 14 times. And it speaks volumes that Pletcher is one of only a handful of trainers who have been able to breath the same rarified air as his predecessor. Pletcher, who is responsible for seven Eclipse Awards and 10 earnings titles thus far, surpassed the then-leading Lukas in lifetime earnings in 2014 before going on to become the first trainer to reach the $300-million mark in 2015.

Soaring With Eagles

Whittingham would make only a brief appearance in the career of the newest Hall of Fame trainer inductee, however, the 'Bald Eagle' would have a far more meaningful influence over another future Hall of Famer. Based on the West Coast, Whittingham annexed a trio of Eclipse titles throughout his career, in addition to leading all North American trainers in earnings on seven occasions. Himself a former assistant to another Hall of Famer, Horatio Luro–best known for training Classic winner and legendary sire Northern Dancer–the Chula Vista, California native would go on to become the all-time leading trainer of stakes wins at both Hollywood Park and Santa Anita. Inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1974, he was responsible for five future Hall of Famers–Ack Ack, Cougar II, Dahlia, Flawlessly and Sunday Silence. Whittingham also guided the careers of champions Turkish Trousers, Perrault, Kennedy Road, Estrapade, Ferdinand and Miss Alleged.

In a career that spanned 49 years, Whittingham served as a mentor to a long list of horsemen and women, and one of the most well known was English transplant, Neil Drysdale. After spending two years with John Hartigan at Tartan Farms in Ocala, Florida, Drysdale worked in Argentina and Venezuela before returning to the U.S. to serve as an assistant to Roger Laurin for two years. He subsequently joined Whittingham as an assistant for five years before going out on his own. Since launching his stable in 1975, Drysdale has trained a trio of Hall of Fame members: A.P. Indy, Princess Rooney and Bold 'n Determined. To his credit, he has won over 1,500 career victories, including the 2000 Kentucky Derby with Fusaichi Pegasus, and the Breeders' Cup on six occasions, including with champions Tasso (Juvenile) and Hollywood Wildcat (Distaff), in addition to Prized (Turf) and War Chant (Mile). Also included among his most notable runners are champion Fiji.

Jumping to Glory

Another English transplant that found success in America, Jonathan Sheppard, who received some of his early inspiration from Hall of Famer W. Burling 'Burley' Cocks (inducted in 1985), who also had a hand in the illustrious career of Hall of Famer Tom Voss (2017). Launching his stateside training career in 1965, Shepperd registered his first victory on the flat, however, he would grow into a powerful force on the American steeplechasing circuit. He led all steeplechase trainers in purses from 1973 through 1990, heading the list 29 times in total. He is also responsible for Hall of Famers Café Prince and Flatterer, in addition to champions Forever Together and Informed Decision. In 2010, he became the first trainer to win 1,000 career steeplechase races, before following up the next year by surpassing the $20-million mark in earnings. Sheppard, who was inducted in 1990, retired from racing in 2021 with 3,426 victories and earnings of $86,679,925.

Ensuring his lasting influence, the Englishman was followed into the Hall of Fame in 2009 by another steeplechase luminary, Janet E. Elliot, the only female trainer currently in the great hall. Serving as an assistant to Sheppard for 11 years, the Irish native went out on her own in 1979, and in 1991, surpassed Sheppard as the leading trainer in purses, ending the 18-year stranglehold of her mentor. Elliott's runners have earned a trio of Eclipse awards with Correggio (1996) and Flat Top (1998 and 2002). With over $8-million to her credit, she also developed 1986 Breeders' Cup Steeplechase winner Census.

Midwest Connection

Marion Van Berg dominated the Midwest, first as an owner, winning over 4,600 races, before assuming the mantle as a trainer in 1945. Leading all owners in number of victories 14 times, Van Berg was also the leading owner in money won four times. Before retiring in 1966 with 1,475 wins, the Columbus, Nebraska native saddled stakes winners Rose Bed, Knights Reward, Estacion, Rose's Gem, Spring Broker and Grand Stand. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1970.

Following his retirement from training, Van Berg's son, Jack, took over the reins, achieving even greater success than his forerunner. After sending out his first winner in 1957, the junior Van Berg was the leading trainer at Ak-Sar-Ben in Nebraska for 19 consecutive seasons, and topped all trainers by number of wins nine times between 1968 and 1986. Becoming the first trainer to win 5,000 races, Van Berg ultimately retired with 6,523 victories and purse earnings of $86 million. Joining his father in the Hall of Fame in 1985, he ranked as high as fourth in all time wins at the time of his death in 2017. Van Berg was responsible for a host of top rung winners, but was probably best known for a pair of Classic winners–Gate Dancer and Alysheba. The former won the Preakness in 1984, the year Van Berg earned the Eclipse Award training title. The latter, won the Kentucky Derby and Preakness, and came back at four to win six Grade I's, including an epic renewal of the Breeders' Cup Classic. After garnering the Eclipse Award as champion 3-year-old male in 1987, the son of Alydar was named Champion Older Male and Horse of the Year at four. He retired with a then-record $6,679,242 in earnings, surpassing the previous record of future Hall of Famer John Henry (1990).

The Van Berg stable was well established by the time a young horseman from Mobridge, South Dakota–Bill Mott–appeared on the scene. A year after joining Van Berg, Mott was promoted to assistant–alongside Frankie Brothers–and the stable enjoyed unprecedented success through the 70s, including a banner campaign in 1976 when Van Berg earned the training title at Arlington Park in addition to leading the nation with 496 wins.

After Van Berg decided to head West, Mott opted to remain in the east, launching his own public stable in 1978. Through the ensuing four decades, Mott was responsible for six champions; Theatrical, Paradise Creek, Ajina, Escena, Royal Delta and most notably, Horse of the Year Cigar, who won a tick under $10 million in earnings before his retirement. Voted the Eclipse Award trainer three times, Mott ranks sixth among all trainers with 10 Breeders' Cup victories and over $19 million in earnings. Mott set a then-record for number of wins at a single Churchill Downs meet with 54 in 1984. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1998.

Creme de la Creme

In stark contrast to Lukas and Van Berg who operated two of the most expansive operations of their era, Frank Y. Whiteley Jr. commandeered a much lighter ship. However, what the Maryland native lacked in breadth, he more than made up for in brilliance and talent. Through a career that spanned five decades, he trained 35 stakes winners, although is best known for his quartet of champions. Arguably the most famous of the group is Ruffian, Champion 2-year-Old Filly of 1974, who became only the fourth horse in history to win the Filly Triple Crown at three en route to another divisional championship. Tragically, while facing 1975 Kentucky Derby winner Foolish Pleasure in a match race on July 6, 1975, the black filly suffered a catastrophic breakdown and was subsequently euthanized.

Although Whiteley never won on the First Saturday in May, he did annex the second jewel in the Triple Crown twice, the first with Tom Rolfe (1965) and later with Damascus (1967), who also added the Belmont. Damascus was inducted in 1974, while Ruffian took her place in the hallowed halls two years later. Whiteley also trained the mighty Forego, a three-time Horse of the Year and winner of eight Eclipse Awards who was inducted in 1979.

Forever etched in history through his equine stalwarts, Whiteley, who retired from training in 1984, also played a significant role in the career of his son David, himself a much-lauded trainer with a select number of runners, and with Barclay Tagg, responsible for dual Classic winning Funny Cide. He is probably best known as mentoring future Hall of Famer Claude 'Shug' McGaughey III. McGaughey took on a public stable in 1979, but it was his tenure as the principal trainer for the Phipps family that would help cement his claim to the Hall of Fame.

Listed among the champions trained by the Kentucky native are Hall of Famers Easy Goer, Personal Ensign, Heavenly Prize, Inside Information and Lure. In addition to those luminaries, McGaughey also conditioned champions Honor Code, Queena, Rhythm, Smuggler, Storm Flag Flying and Vanlandingham. Earning the Eclipse Award in 1988, McGaughey collected his first Classic victory in the 1989 Belmont with Easy Goer before capturing the Run for the Roses in 2013 with Orb. With nine Breeders' Cup victories already to his credit, the 70-year-old has collected over 2,100 in victories and earnings in excess of $155 million, ranking him 10th among top active trainers. He was inducted in 2004.

All In the Family

The 2007 inductee, John Veitch, holds the distinction of having served as an assistant to not one but two Hall of Fame trainers–his father Sylvester, who was inducted in 1977 and John Elliott Burch, who earned his own admission in 1980. Both generations of Veitch men had the opportunity to train for some of the most influential stables of their respective eras. The elder Veitch, arguably best known for training C.V. Whitney's champion juvenile filly First Flight and George Widener's What A Treat, 3-year-old champion filly of 1965, also developed Classic-winning champions Phalanx (1947) and Counterpoint (1951). A third generation horseman, the junior Veitch trained a pair of Hall of Famers–Calumet runners Davona Dale and Alydar–in addition to champions Before Dawn, Our Mims and Sunshine Forever during a career that spanned three decades. Veitch also won the second renewal of the GI Breeders' Cup Classic with Darby Dan's Proud Truth.

Another third generation horseman, Elliott Burch, succeeded father Preston M. Burch (1963) and grandfather William P. Burch (1955) into the Hall of Fame. The most recent inductee, Elliott Burch trained six champions and four members of the Hall of Fame–Horse of the Year Sword Dancer, Arts and Letters, Bowl of Flowers and Fort Marcy. Owner, breeder and trainer Preston Burch developed stakes winners both on the flat and over the jumps in the U.S., Canada and throughout Europe. The breeder of Hall of Famer Gallorette, he took over training duties on 1916 Kentucky Derby hero George Smith, and later defeated Derby winners Exterminator and Omar Khayyam in the 1918 Bowie H. Burch also won the 1951 Preakness with Bold. Heading the Burch trifecta is William Burch, who was among six inductees during the initial round of admissions into the Hall of Fame in 1955. Among the notable horses trained by Burch were Wade Hampton, Burch, Telie Doe, Biggonet, Inspector B., Mart Gary, Grey Friar and Decanter.

One can count on one hand the number of trainers who can boast having had a single Triple Crown winner in the barn, but the father-son duo of Benjamin A. Jones (1958 inductee) and Horace A. 'Jimmy' Jones (1959) were blessed with a formidable pair courtesy of Calumet Farm–Whirlaway (1941) and Citation (1948). The elder Jones conditioned six Derby winners, including Lawrin, Pensive, Ponder and Hill Gail, and was also the trainer of record for Citation's Derby score, however, it was widely understood that his son, Jimmy, actually campaigned the champion colt through his Horse of the Year season. Following in the footsteps of his father when assuming training duties for the powerful Calumet stable, the junior Jones was responsible for seven champions, including Armed, Coaltown, Bewitch, Two Lea and Tim Tam, all of whom are members of the Hall of Fame. The leading money earner five times, Jones was the first trainer to surpass the $1-million mark in a single season in 1947.

Another name synonymous with racing excellence is the Hirsch family, represented by Maximillian (Max) J. Hirsch (inducted in 1959) and William J. 'Buddy' Hirsch (1982). Armed with a slew of powerful patrons, the elder Hirsch dominated the Classics, winning nine from 1936 through 1954, including sweeping all three with King Ranch's Assault (1946). The Texas native also conditioned Classic winners Bold Venture, Middleground, Vito and High Gun.

Supporting the old adage that 'the apple doesn't fall far from the tree,' Hirsch's daughter, Mary, became the first woman to be granted a trainer's license in the U.S., and his one-time assistant and son, Buddy, would follow him into the Hall of Fame. Earning a Bronze Star and Purple Heart while serving in the Army, Buddy continued to train for many of the names that would help define his father's training career. In addition to King Ranch, Hirsch's stable of owners included Alfred Vanderbilt, Greentree Stable, Edward Lasker and Jane Greer. Standing atop his leading runners was King Ranch's Hall of Famer Gallant Bloom, champion juvenile and 3-year-old filly. The California native also conditioned To Market, Triple Bend, Intent, Rejected, Golden Notes, Cyrano and O'Hara.

Also continuing along family lines, Texas-born George Carey Winfrey, who apprenticed under Hall of Famer Sam Hildreth, launched his own stable in 1917, and through almost five decades, won 940 races and over $2.4 million in purses while never having more than 10 horses in his stable at once. He was succeeded by his stepson, William C. 'Bill' Winfrey, who developed Alfred Vanderbilt's Hall of Famers Native Dancer and Bed o' Roses, in addition to champion Next Move. Born in Detroit, Michigan, Bill Winfrey later took over the powerful Phipps stable following the retirement of Hall of Fame trainer 'Sunny Jim' Fitzsimmons, and developed champions Castle Forbes, Queen Empress, Bold Lad and Buckpasser, who entered the Hall of Fame in 1970.

Branching Out

A handful of candidates come to mind that are likely to give rise to a new Hall of Fame branch, however, arguably none more so than Chad Brown. After working for a time with McGaughey during his college years, the native of Mechanicsville, New York joined the powerful stable of legendary Hall of Famer Bobby Frankel (inducted in 1995) in 2002. Venturing out on his own in the fall of 2007, it didn't take long for the young trainer to earn his first graded stakes win with Maram in Belmont's GIII Miss Grillo S. The 2-year-old filly went on to annex the GI Breeders' Cup Juvenile Turf Fillies at Santa Anita later that fall. Since then, the 42-year-old has earned the Eclipse training title four times, has developed 10 Eclipse champions, including Horse of the Year Bricks and Mortar. Ranked just behind Frankel in seventh with career earnings over $204 million, he has also accounted for 15 Breeders' Cup wins to date. And although yet to win the Kentucky Derby, Brown has registered a win in the Preakness, taking the race with Cloud Computing in 2017.

Like the Pletchers and D. Wayne Lukas' of the world, many of the most high-profile trainer/assistant teams to enter the great hall are typically fairly easy to single out long before their induction. However, it remains just as likely that several more names that escaped mention could have also been added to the expansive list of horsemen herein. And what might future iterations of the Hall of Fame tree look like? Arguably, not a whole lot different than it does today. Because, while the source of experience and the breadth of accomplishment may vary vastly among the horsemen and women already bestowed the great honor, the constant remains the ability to absorb the best gleaned from previous generations of masters, and to roll that into a winning formula that is successful in a contemporary world. And for 99 trainers in the Hall of Fame, it is a fait accompli.

The post Hall of Fame Assistants appeared first on TDN | Thoroughbred Daily News | Horse Racing News, Results and Video | Thoroughbred Breeding and Auctions.