What does the most recognizable jockey of the nineteenth century have in common with a young rider from the 1970s-turned-modern-day playwright? This seemingly disparate pair might be divided by over a century along the continuum, but their experiences, told in a fresh biographical treatment of Isaac Murphy by historian Katherine C. Mooney and through Robert Montano's self-penned and deeply-personal play, have much to tell us about the perilously-seated life in the irons.

What they both encountered is particularly instructive for us, especially after the sudden and tragic losses of jockeys Alex Canchari a few weeks ago and Avery Whisman in early January. Their deaths serve as a living reminder about the fragile and destructive nature of inner pain. As mourning for the 29-year-old Canchari and 23-year-old Whisman takes its course, perhaps what's helpful at this point is to try and take a step towards making sense of it all. By no means does that guarantee a panacea, but what we do know is that different mediums can help us digest, reflect, learn and process.

Murphy's Weight

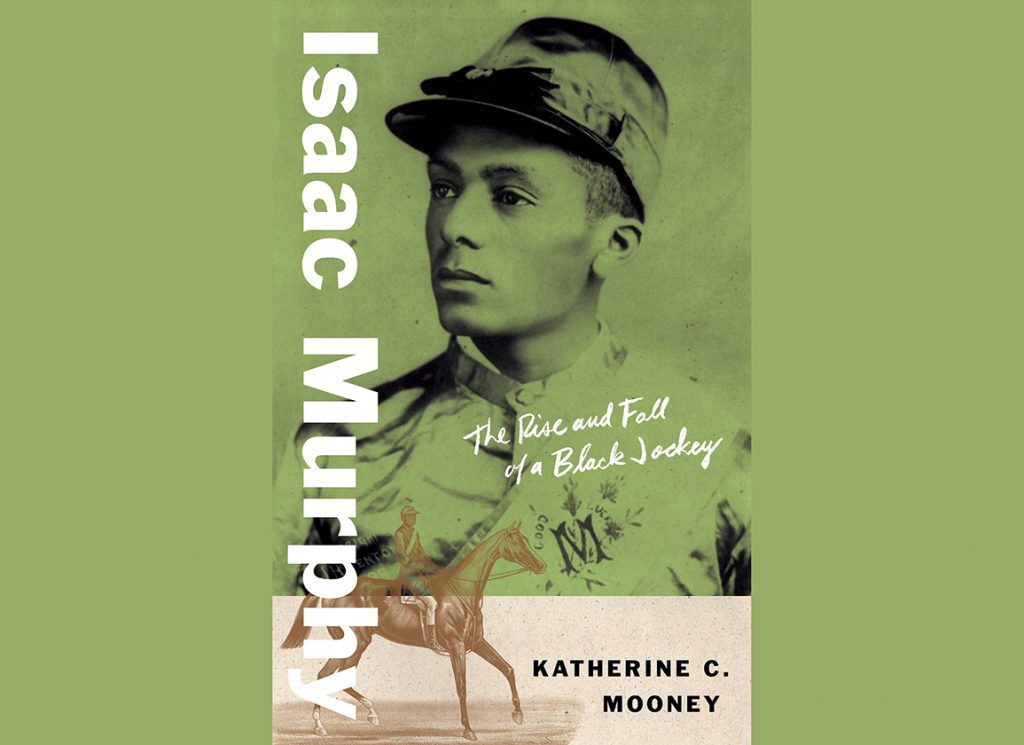

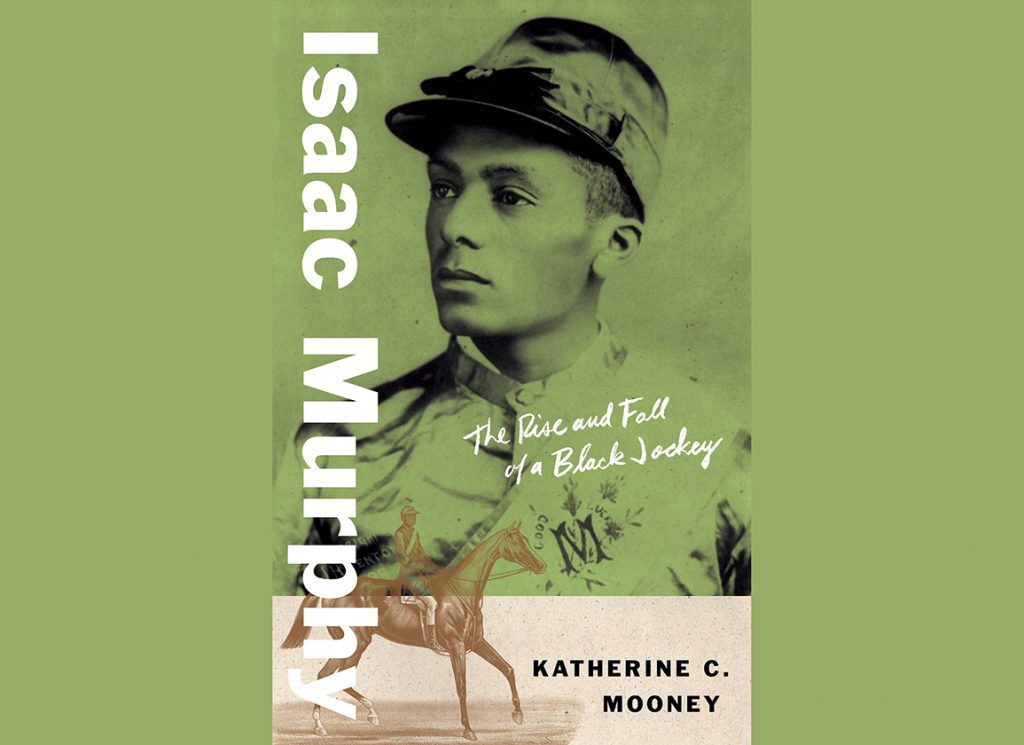

First, Mooney's forthcoming monograph entitled, Isaac Murphy: The Rise and Fall of a Black Jockey published by Yale University's Black Lives series, covers fresh ground concerning the life of a rider who transcended race in Jim Crow America as he won impressively against white jockeys at racetracks from New York to Kentucky to California in the 1880s and into the 90s. As Mooney so eloquently and sadly described in her excellent Race Horse Men: How Slavery and Freedom Were Made at the Racetrack (2014), Black horsemen were driven from the sport as new laws were passed affirming the power of white rule. They never returned, but to this day, they have not been forgotten. If you have not read it and you love this sport, you are missing something.

Isaac Murphy: The Rise and Fall of a Black Jockey by Katherine C. Mooney | Yale University Press

This time the author focuses her attention on Murphy, a celebrated athlete who as a household name, inspired people from different racial and socio-economic backgrounds to root for him. That was the public form of his persona, the one where his ability to effectively cross the color line was based in what appeared to be a bottomless pit filled with drive and determination as he won. With a come-from-the-clouds riding style, which reserved his mount's strength until the last possible moment, Murphy's final approach thrilled the masses.

Mooney also gives a window into the private person who rarely gave interviews or left much of a record concerning his health. That might be just as instructive because throughout his life aboard some of the best Thoroughbreds in North America, he continually battled “making weight.”

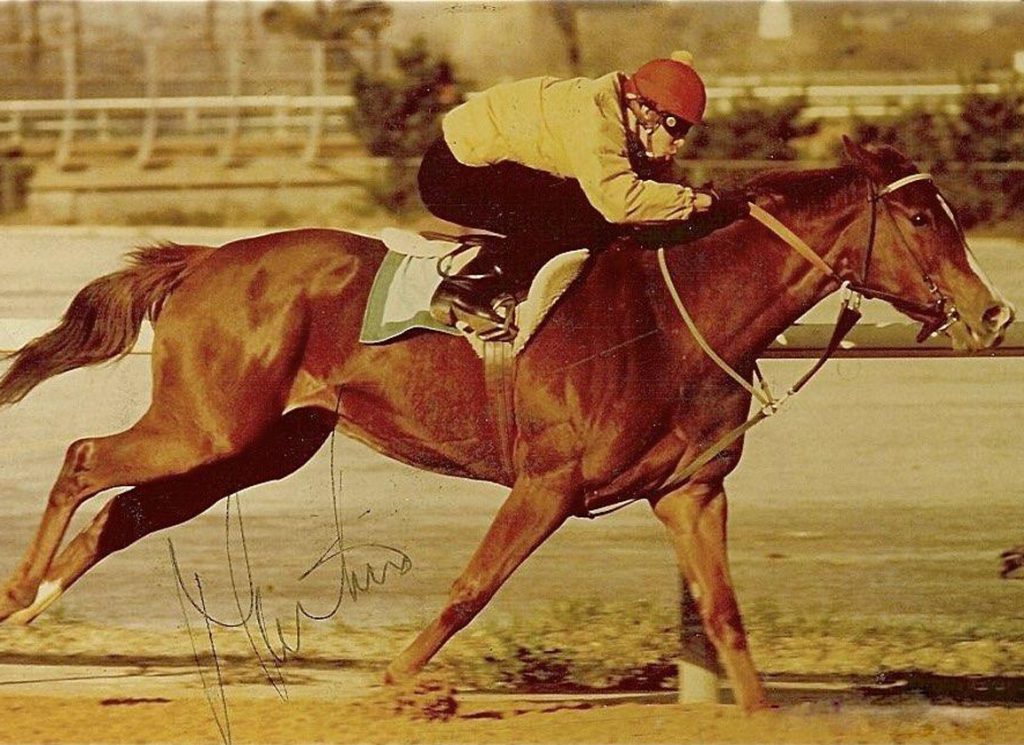

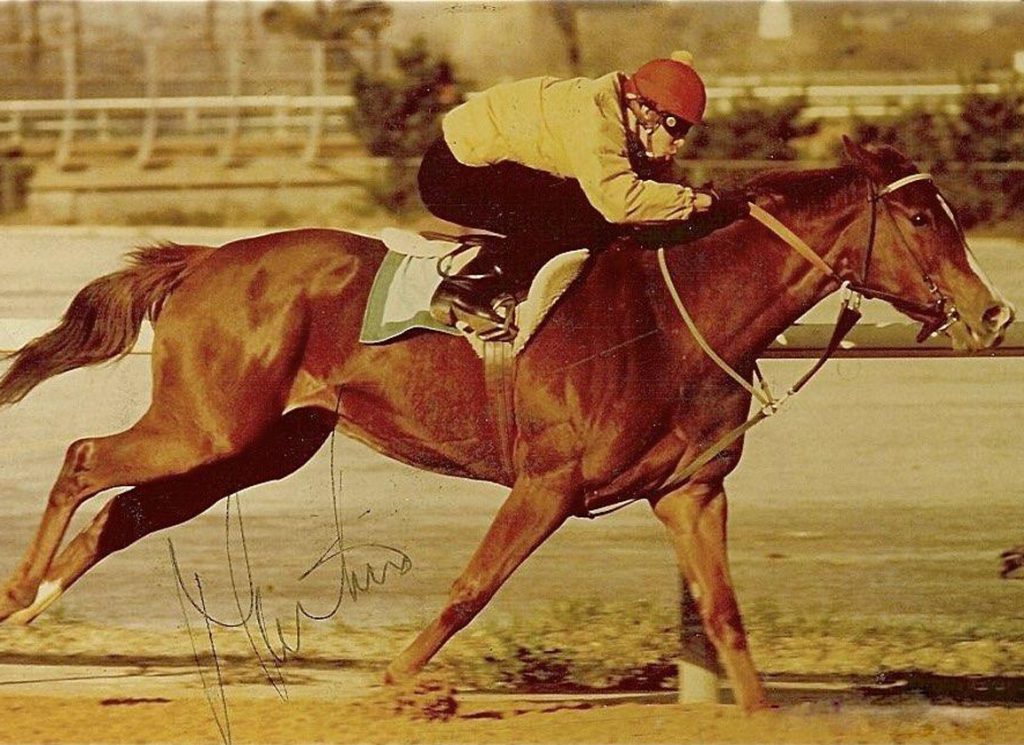

Tenny with jockey Isaac Murphy | Keeneland Library

It took its toll.

Not just a seasonal rider, Murphy traversed the country working as often as he could under contract for a specific owner, supplemented by freelancing. Though he garnered what today would be the equivalent to million-dollar earnings, he continually scrambled throughout his riding days to go from 140 pounds all the way down to a dangerously low 110.

Mooney tells us, despite his successes, the regularly mentioned three Derby wins stat, et cetera, that Murphy was plagued later in his career by innuendo that he rode under the influence of alcohol. Racing in the 1890 running of New Jersey's own Monmouth Handicap aboard the seasoned mare Firenze as the favorite at 6-5, the pair ended up last with the jockey falling off after he crossed the wire. Shock and awe fell over the capacity crowd and in a subsequent hearing, Murphy explained that he had skipped breakfast that morning, drinking a few milk punches, regularly understood to be medicinal during the age. Later that day, with his wife by his side in the grandstand, he got down ginger ale and mineral water, in what was hardly the stuff for a balanced diet.

Author Katherine Mooney | Christopher T. Martin

Despite his impressive horsemanship, just to get into the saddle took a monumental effort to fight time and his own metabolic rate. Murphy had the desire and knew that back home in Lexington, Kentucky, his family was relying on him to provide. In the end, it was heart failure that ended his life at the age of 35-years-old. The demands of the profession exacted a terrible price. As Mooney prophetically explains, “Jockeys were ultimately dependent on the people that employed them.”

Montano's Stage

Like Isaac Murphy, Robert Montano was born for a stage. As a dancer and actor from the playhouse to the screen, he's worked with the likes of Chita Rivera to Mark Wahlberg. Growing up in Hempstead, New York in the 1970s with parents who dared their kids to dream, one afternoon his mother took the 12-year-old to Belmont Park. She told her son they were there to “pick out tiles for the kitchen floor,” code for a hopeful wagering result. Montano was captivated by the pomp and circumstance. Immediately, seeing the reverence held for the jockey colony, he was hooked.

“Working and learning from those professionals had such an impact on me, and their toughness and discipline set me on a path I am still on today,” he said. “Robert Pineda taught me about balance in the saddle and he really took me under his wing as a teenager, giving me a shot to ride.”

Robert Montano working a horse as an exercise rider | Robert Montano

Montano's ticket to the backside was a neighbor and his wife who both worked at nearby Belmont Park. They got him a job cutting carrots, which is where everyone begins. Eventually, he graduated to exercising riding there and at nearby Aqueduct Racetrack, but the life that was running concurrently with his high school days was anything but normal.

Like every budding apprentice, the fresh-faced young man agonized over his weight. His commitment pushed him to do endless laps around his neighborhood, while later he sweated in the local YMCA sauna clothed in jackets and sweaters, as burly guys looked on in astonishment. Still, he dreamed about donning silks that would make him a full-fledged member of the New York racing colony.

Just like the professional dancer he would become, health became an all-encompassing focal point for Montano. He was tempted though by the darker side of losing weight as he sought out the “Doc” who saw patients near the local Argo Theater. Appetite suppressants were downed and when his art professor father found out, he told his son, “No more, this is not how to pursue your dreams.”

With Pineda serving as mentor, he finally got his first mount in an actual race at the ripe age of 16. It was March 2, 1977. But there was a problem. That morning at Belmont he fell off a horse during training and badly bruised his ribs. At the Emergency Room, he begged the attending physician to patch him up, and pleaded his case with his parents who wore worried looks. Put back together and heavily bandaged, he made it in time for the race, finishing last. “Despite some serious pain, that was a huge moment for me and I loved every minute of it,” he said.

Robert Montano heads to the post | Robert Montano

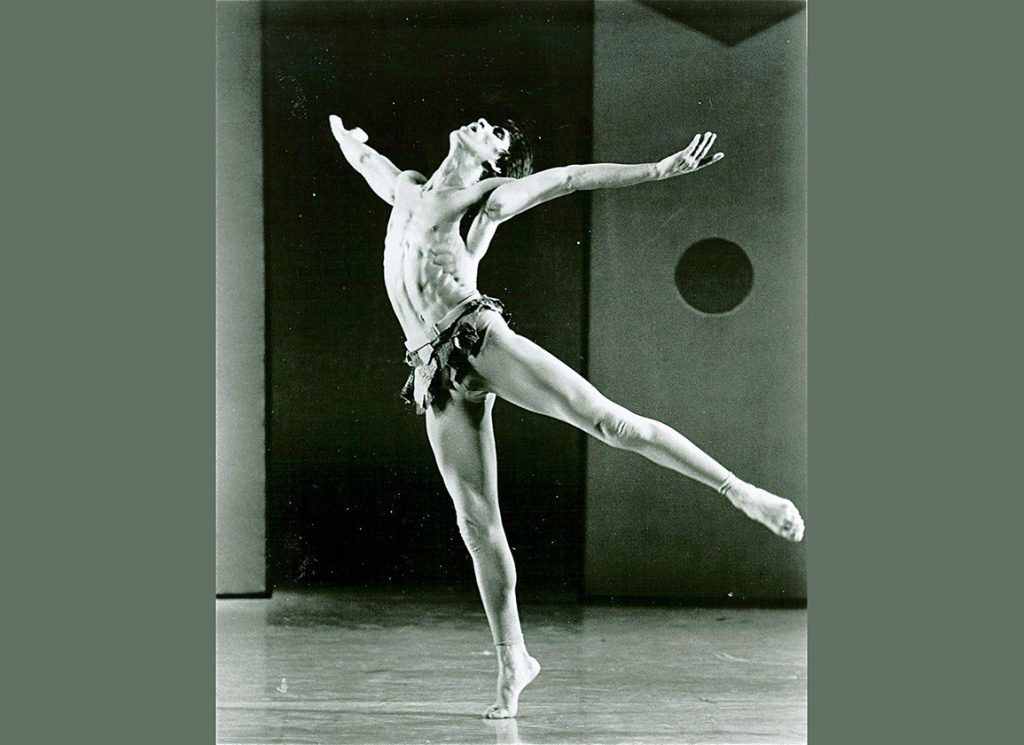

Montano only rode six other times, never in-the-money, and though time and genetics were against him, those experiences put him on another track. At the age of 20, he earned a scholarship at New York's Adelphi University to enter the world of dance and theater, another place where showmanship is held in high-esteem.

As his new career blossomed, he came across a director who asked him about his first love. “The racetrack,” he said, without hesitation. “You should write something about that experience,” the director told him. So, after years of writing and delving into feelings that he had not touched since those early days, he did.

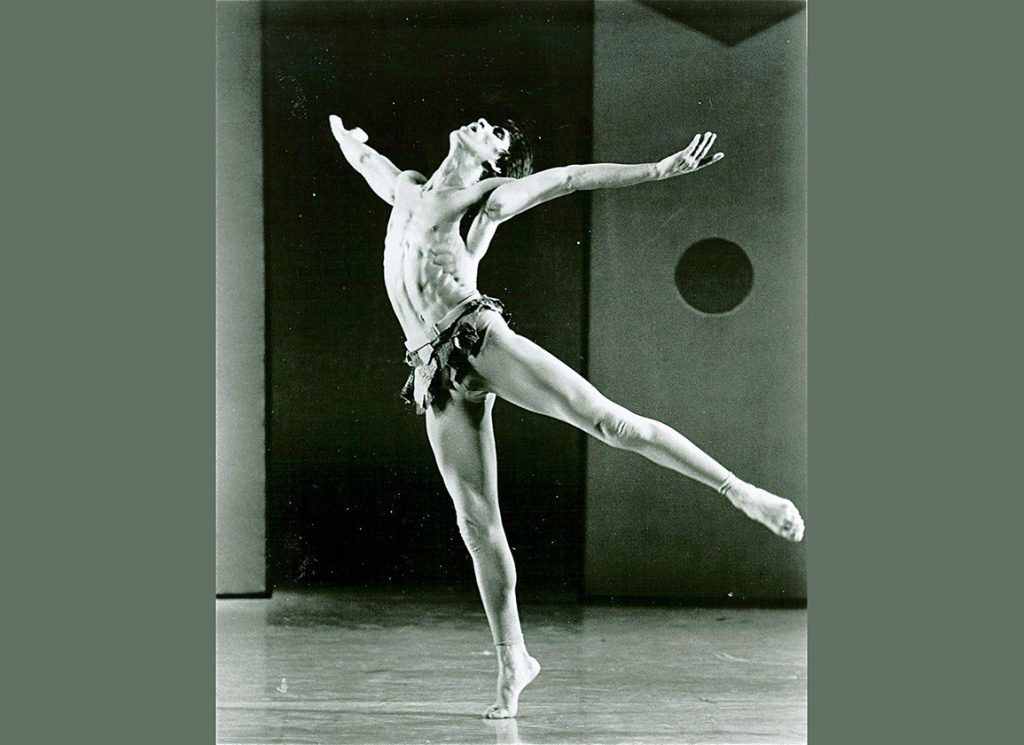

Robert Montano on the stage at Adelphi University | Robert Montano

This week on the campus of Kean University in Hillside, New Jersey, Montano's SMALL, which premiered at the Penguin Rep Theatre in Stony Point, New York last year, will take the stage. Performing 24 different parts, he will morph and change into the characters that surrounded his life as he pointed towards adulthood. As he says, “SMALL is about my duty to give the audience an authenticity and it is the chance to honor those that are associated with this great sport.”

With a title that is purposely capitalized, Montano's play examines his personal struggles to stay small, as he fought addiction and to find his place in the world. Now a performer of a different sort, he lends his own perspective from the saddle in the form a play. Using the visceral experiences of his youth, SMALL has the opportunity to loom large.

The Fight to Ride

Whether jockeys ride seven races or 7,000, they are bound by the pursuit of a profession that demands abject discipline. While the job offered the opportunity to stoke pure unadulterated talent, both Katherine Mooney's biography of Isaac Murphy and Robert Montano's SMALL, suggest how the challenges aboard a horse are balanced by their love of the racetrack. Lest we forget, sadly Alex Canchari and Avery Whisman's lives ended pursuing passions while trying to cope with inner pain. As those in the irons pass into our memories, we would do well to remember that their struggles are real and not the stuff of fiction. Both of these mediums might be just what we need at this juncture, as they suggest that across a swath of time that the names may change, but what Montano so aptly calls, “The fight to ride,” remains.

Isaac Murphy: The Rise and Fall of a Black Jockey by Katherine Mooney, Yale University Press, 177 pages, photos, appendix, glossary, May 2023.

SMALL by Robert Montano, co-presented by Premiere Stages and Kean Stage, directed by Jessi D. Hill, Saturday, March 18 at Kean University's Enlow Recital Hall, 215 North Avenue, Hillside, NJ 07205.

The post Mediums Evoke The Jockey’s Fight To Ride appeared first on TDN | Thoroughbred Daily News | Horse Racing News, Results and Video | Thoroughbred Breeding and Auctions.

Source of original post