Editor's note: This column is the first in our new series about the strides horse racing is making to advance the ethical treatment of racehorses.

On many levels, those in horse racing and breeding are working to ensure the sport is humane and ethical. New studies and standards about track surfaces, stress, medications, diagnostics and more, shed light on how to ensure the safety and comfort of racehorses. Enforcement of anti-doping regulations has reached a new level with better use of surveillance, hotlines and other anti-crime tactics. And in the U.S, there is a major attempt at regulation uniformity and centralization of enforcement efforts.

Good horsemen will tell you it's important to have a horse in a positive mindset no matter what you ask of him or her. The use of force, fear and intimidation to make a horse comply are not only seen as inhumane and unethical by today's moral standards, but are ineffectual.

But one big question remains: how do we ensure that horses are treated humanely and ethically by the people who handle them every day at the barn and on the track?

A good groom can be the companion that a horse needs in its unnatural lifestyle on the track. But a frustrated, fearful or untrained groom or hotwalker can be a daily living nightmare for a horse.

In more than one way, the starting gate is where the 'rubber meets the road' as far as the relationship between humans and horses on the racetrack. To successfully enter the race, a horse must safely enter the starting gate, stand quietly (sometimes for several minutes) and then break from the gate efficiently. This process is often done on television in close-up where millions of people can see it go well or go badly.

In the not-too-distant past, horses were often dragged, pushed, punished or tricked into going into gate, after spectators witnessed an unfortunate battle of wills between the assistant starters and the fearful, reluctant horse. When a horse is in the wrong mindset, the gate is a dangerous place for the horse as well as the rider and the assistant starter. If the horse does get through the process of being forced into the gate, it will likely break and race on an adrenaline rush, the least optimal way to perform in the race.

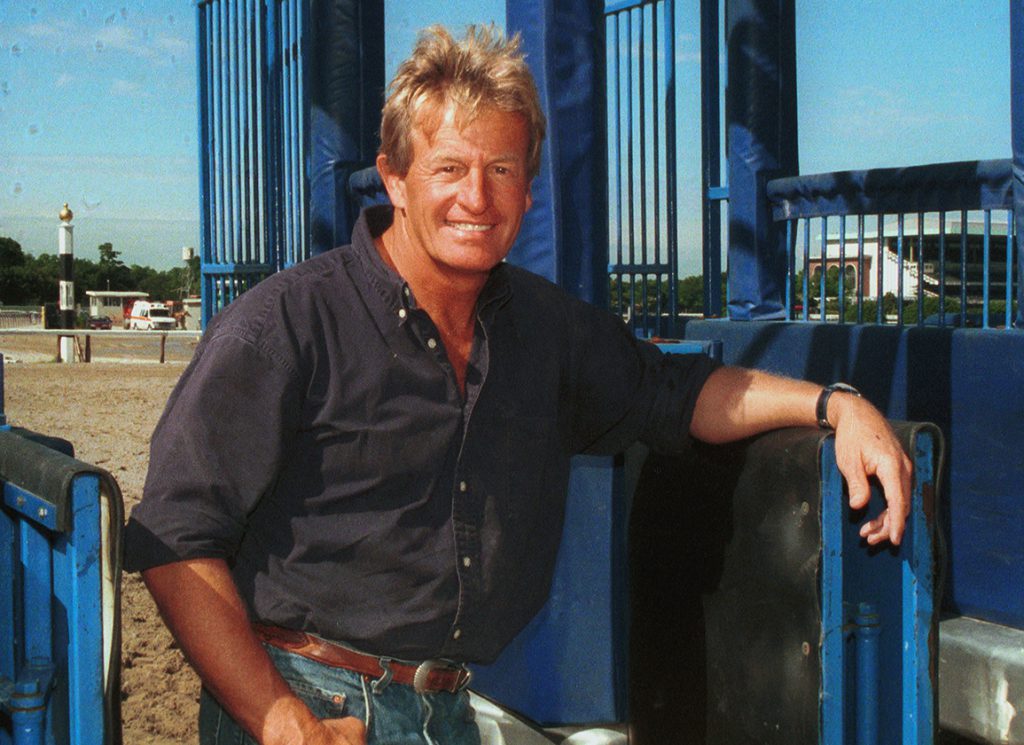

We asked retired New York Racing Association (NYRA) Head Starter Robert (Bob) Duncan, renowned for his success at transforming starting gate protocol, to talk about his experience in running the gate-schooling and starting-gate program at NYRA and how he came to be a proponent of natural horsemanship at the gate and throughout all elements of the training, racing and breeding process.

TDN: You are credited with revolutionizing the starting gate process. What about your experience on the gate caused you to go on that quest?

RD: During my early years as an assistant starter, we had been following traditional methods of gate work that often called for more insistent ways to get horses into the gate with the intention to mimic the pace of the race day experience. When coaxing failed, we would, at times, resort to using force, fear or mental intimidation. This caused the horses to become fractious, and at times explosive. So, we found various ways to restrain and contain them. We were treating the symptoms but not the disease. Frustration led to anger and escalation as we had no understanding of the instincts or needs of the horse.

I liken it to being a five-year-old entering school for the first time only to find out that everyone there spoke a different language than you. The school is spooky and the classroom is loud and crowded with threatening-looking people who speak gibberish. When you don't respond to their instruction, they get frustrated and speak louder and louder at you. Now they are surrounding you with angry expressions on their face. Now they start pushing you then slapping you while you struggle to figure out what they want. You feel like your life is being threatened and you want to escape.

TDN: What changes did you first implement in your experiment?

RD: While still a foreman, I was given the freedom to take a fresh look at our gate procedures with an eye toward finding more horse friendly ways of preparing horses at the gate.

Traditions die hard, especially in the insular world of horse racing. For instance, when I started on the gate, the wisdom of the day was that horses had to be wound “tight as a watch” to give their best efforts at leaving the gate. Horses were drilled from the gate with bells ringing, doors slamming and a slap on the rump if there was a moment's hesitation. Truth is, horses are taught to react to the movement of the front doors. All the other commotion is background noise. If the horse needs to react to the bell, he missed the break because the bell rings a split second after the doors open.

The changes started with us slowing the schooling process down and allowing the horses the time and environment to learn the gate process in an unthreatening way. We also broke from the old “one size fits all” regimentation and concentrated on each horse as an individual needing particular care.

We started to see improvements. The atmosphere at the gate was calmer, more conducive to learning. But we were still stumbling along like a blind pig searching for an acorn.

Also, in the early stages much thought was given to making the gate more habitable. More padding was added to the stall space at the horses' hips to stabilize them as they reset their feet at the start. The extra padding reduced stumbling. It also prevented knee injuries that were so common among gate crews. (When a horse broke awkwardly, it often drove its hip into the assistant's calf, torqueing the knee.) The Japanese Racing Association had an interesting schooling gate at its Mijo training facility. Stalls were graded from a large walk-through stall down to an actual racing stall, allowing their horses to acclimate to the constriction of the small racing gates. All our schooling gates now have a similar adaptation.

Later, as I learned the natural body language of horses and how to establish oneself as a leader worthy of a horse's trust, we changed our approach and steps to gate schooling. We no longer needed buggy whips, forceful loading from behind or even, except in the rarest of cases, blindfolds.

TDN: Were those initial changes acknowledged and well received?

RD: Word of our changes started to get around and we found trainers to be less resistant when asked to school a problem horse. Joanie Lawrence, a friend of mine who worked at The Jockey Club offices in NYC, called one morning, to ask if she could come out to Belmont to write an article about what we were doing.

Joanie's one page article was read by Stu Kirshenbaum, a television short films producer for Winner Communications. He brought a crew out to do a short piece on our “new” methods and the ball started rolling. To this day, I credit Joanie for opening up a life-changing world to me that I didn't know existed.

Later in that same summer of the short film, the legendary horseman Monty Roberts sought me out at the races in Saratoga. At the time, his book, “The Man Who Listens To Horses”, was on a long run at number one on the New York Times best seller list. Monty was in Saratoga for a book signing but he had seen the piece we did and he was impressed. He complimented the crew and proceeded to invite me out to his Flag is Up Farm in Solvang, Ca. A couple of weeks later, in early September, I received a letter from the University of Arizona, asking me to participate in the Symposium on Racing. Tom Durkin moderated and Monty Roberts was also on the panel. Directly after the Tucson panel, I went to his ranch to be a part of his work with a horse that was having 'severe gate issues.'

TDN: What were some of your “aha” moments as you developed this knowledge and plan?

RD: The first of many aha moments occurred the next spring after the Tucson conference. Monty called to invite me to a demonstration he was doing in Topsfield, Massachusetts. My 15-year-old son David was with me. Monty had us placed in the arena in the front row of a small group of people that surrounded a round pen. The arena behind us held a couple thousand people. Monty explained that the horse he invited was a 14-year-old mare who had never loaded into a horse trailer without being staggeringly tranquilized.

A step-up trailer was backed into the opening of the pen. It was easy to see that the mare was on edge in these unfamiliar surroundings with a fairly vocal crowd. Monty held a coiled line that was snapped to the mare's halter. While he spoke, he asked the mare to step backward and then forward, using only as much pressure on the lead line as needed to get a response. The second she responded, he released the pressure. With each ask, he became lighter, eventually just barely leaning towards her and she quickened in her response until it seemed they were connected with an invisible thread.

He paused for a moment and asked someone in the immediate area to note how long it took to load the mare. With that Monty turned, dropping lengths of the lead to the floor, and walked briskly toward the trailer. Even before the slack went out of the rope the mare hustled up behind Monty following him directly into the step-up trailer, turning inside and hanging her head over Monty's shoulder. It was a show stopper.

He finished his demo by asking the crowd not to applaud just yet. He then unsnapped his lead and walked back to the far side of the arena. He said when I tip my hat you can applaud. He did so and at the burst of applause the mare hopped out of the trailer and ran over to Monty hanging her head over his shoulder again. It was all about the mare accepting Monty as a leader and finding safe haven with him. With his technique of creating a connection with her, she found a leader she could understand and trust. He was speaking her language.

This was exactly what I had been searching for. This was an unspoken language that all horses understood. David and I drove back to Belmont late that night. We went straight to the starting gate and napped until the first two horses showed up to school.

We snapped a lead on each one and mimicked the moves that Monty used. It worked so well that both horses almost jogged into the starting gate. We were on our way.

In Wednesday's TDN: Part II of Ethics: A Case for Teaching the Language of Horses

Diana Pikulski is a partner at Yepsen & Pikulski Public Affairs, and a former criminal defense attorney who served as the first Executive Director of the Thoroughbred Retirement Foundation. She is married to Bob Duncan.

Watch Alayna Cullen's 2017 interview with Duncan below:

The post Equine Ethics: A Case for Teaching the Language of Horses appeared first on TDN | Thoroughbred Daily News | Horse Racing News, Results and Video | Thoroughbred Breeding and Auctions.