Editor's note: Ethics is a critical reflection on how we should act and why from a moral point of view. Animal ethics studies how and why we should take nonhuman animals into account in our moral decisions. Because of public pressure and increased understanding on the sentient nature of animals, use of animals in sport and entertainment is being questioned in a way like never before. In this new series, Equine Ethics, Diana Pikulski, a former criminal defense attorney and Executive Director of the Thoroughbred Retirement Foundation, takes a look at the ways that people in racing are changing long-standing practices for the betterment of the horse.

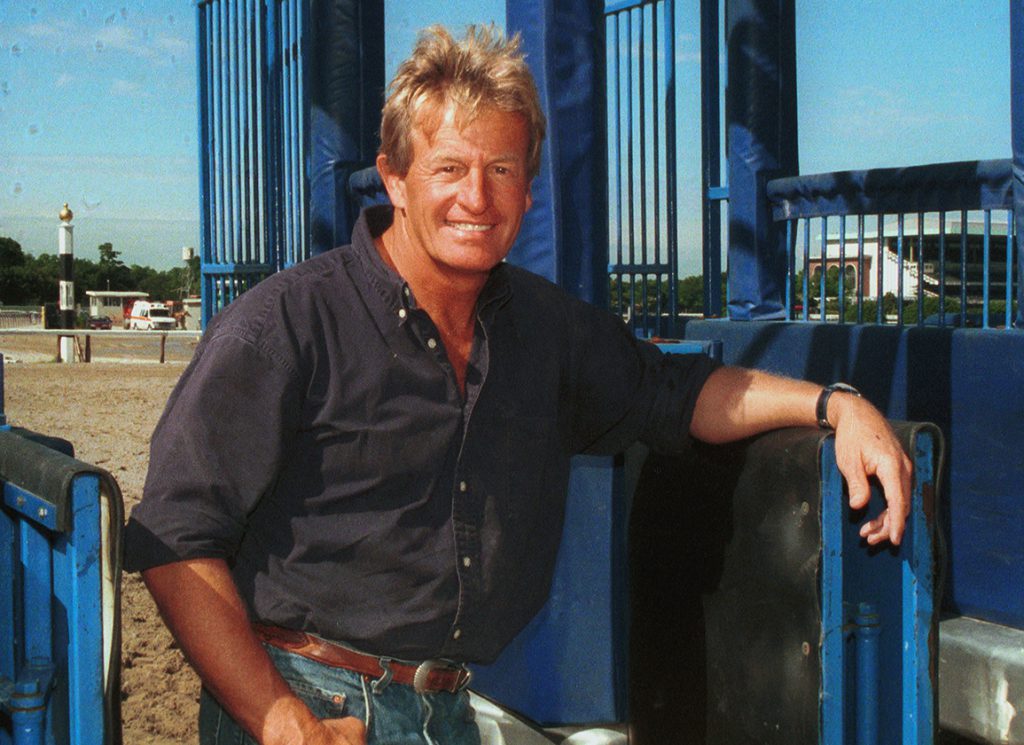

Savvy Racing was launched by Rhett Fincher and his late wife Theresa in 2018 as their concept to train and race Thoroughbred racehorses to success in an ethical manner. Fincher is not new to racing. In fact, he was born into it. His father, Leroy Fincher, was a jockey and now trains racehorses and his mother, Leslie Fincher, was a trainer. His brother Todd rode races for several years and is now a successful trainer.

“I always enjoyed being an exercise rider and rode the tough horses that other riders couldn't manage,” said Fincher. “My goal was to be a jockey. I rode some races, mostly Quarter Horses, but then I realized that I was going to be too big to do that. So, I needed a new plan.

“I figured I would work for different trainers and put together the best of what each of them knew, but that was disappointing because no one really knew the answers to the 'why' questions. Why do we do this? Why do we do that? Why do we use that bit? So, I did what they did. I tied the horses' mouths shut. I shortened my reins. But I realized that this was bad and not going to get any better.”

Fincher then started looking to trainers in other disciplines where the horses were performing and competing but who seemed more relaxed in their jobs.

“I looked to rodeo clowns whose horses were doing tricks at liberty, and watched sessions in natural horsemanship where horses were loose and willingly engaged with people and other horses,” said Fincher. “I thought this must not work with Thoroughbreds or these trainers would be in racing where all the money is.”

Realizing that he was going to have to apply his efforts full time to learning a better way to communicate with horses, Fincher devoted himself to training in natural horsemanship, which can be defined as training horses through communication based on how a horse interacts with others in a herd, horse behavior, horse anatomy, and the evolution of how horses came to be partners with humans. Contrary to what Fincher first believed–that natural horsemanship would not apply to Thoroughbred racehorses–he found every indication that it would.

Savvy Racing is a racing partnership based on horse training methods that can resolve the ethical dilemmas that can plague the sport. While it is still in the experimental stage (its first homebreds have just turned two but will not race until they are three), Fincher is finding success in the mature horses owned by Savvy that are training and running with the speed and over the distance required to win races.

Savvy's website reads, in part: “[Savvy Racing] programs are based on a foundation of principles that puts the horses' needs first by developing a connection with the horse, mentally, emotionally, and physically with the long-term welfare of the horse in mind. Hence our mission is to race our horses with no whips, chains, or performance-enhancing drugs while always keeping the horse's dignity intact.”

“It is about the relationship,” said Fincher. “In the relationship, the horse has four responsibilities: don't change gaits, don't change direction, look where you are going, and act like a partner, not a prey animal.

“Our responsibility is to act like a partner, not a predator. And, to have independent feet and independent seat. Sit and stand in neutral and be part of the flow of energy, not an impediment.”

When the rider and the horse are in sync in their relationship, the horse wastes no energy on fear and runs with confidence and fitness as opposed to adrenaline. In Fincher's mind, emotional and mental fitness are vital to success.

“Horses that are running in opposition to the rider are wasting energy,” said Fincher. “Their energy is not being used in a productive way. They are not using the muscles that they need to run effectively in a race.

“Unlike a horse that is running a race off adrenaline, a horse that is connected to its rider as a leader stays in its bubble with its rider and looks to the rider for its cues. No energy is wasted by taking cues from the other horses in the race. And no energy is wasted by pulling against the rider's hands.”

Continued Fincher, “Racing and training for a horse is just a pattern. Horses know that they come out of their stall, do this pattern, get the hard part over and then go back to the barn. Our horses are trained to be in a herd with the rider–connected to the rider and the rider is the leader.

“When the horse knows his job, he or she ignores all other stimuli and waits for direction, how fast, how slow. You set the throttle and then change speed accordingly. Pulling on the horses face constantly to keep the horse in control is the worst thing that you can do to a horse's performance.”

When it comes time to race a Savvy Racing horse, Fincher said he would hire a jockey who is trained to ride and communicate in harmony with the program's principles.

“He or she will learn,” said Fincher. “We don't pull. We need a rider who is in the program because riding different horses, not trained this way, will be difficult. A rider on one of our horses can't just pick up the reins and apply pressure.”

Veteran exercise rider Valerie Buck, who worked for Hall of Fame trainers D. Wayne Lukas and Todd Pletcher, among others, rode sets with Fincher in Ocala this past spring.

“It's definitely different,” said Buck. “We walk to and from the track on a loose rein. When the horse gets up and going, we have contact and we work like we do with any other horse. But it just feels much more balanced and when it's time to slow down, I just stop riding and the horse relaxes. Then the horse blows out and is totally relaxed again for the walk home.”

Savvy Racing has some initial investors and Fincher is hoping to attract many more. One Ocala couple, Claudia and Bill Parkhurst, who know Fincher from his connection to natural horsemanship training, have joined the syndicate and spent mornings this spring watching the horses work.

“We really enjoy horses,” said Claudia Parkhurt. “We believe in the world of natural horsemanship training and we are curious to see if will transfer to Thoroughbred racing. We love to see the relaxation and the confidence in the horses on the track.”

“Technically, this is still an experiment,” said Fincher, now back at his home base in Arkansas. “Once we realize, as a society, that animals–in this case, horses–deserve more attention to their brain, and we treat them in a way that makes them thrive with confidence and curiosity, there will be no turning back. Racehorses will be happy, well-adjusted and the people who work with them will have positive relationships with the horses, never confrontational and abusive.

“If you love horses, and love racing, this is where it is going to go.”

For more information, visit savvyracingllc.com.

The post Equine Ethics: Savvy Racing appeared first on TDN | Thoroughbred Daily News | Horse Racing News, Results and Video | Thoroughbred Breeding and Auctions.