“When you figure it out, let me know.”

Those were the parting words of a highly esteemed breeder this week, after we exchanged a few thoughts on the diminishing viability of stallions once they have covered their first book of mares. Not that “diminishing,” as an adjective, is really equal to the case. I suppose you could diminish down a lift shaft, but it wouldn’t be the first word that would occur to you in the time available.

Spoiler alert: I haven’t figured it out. But I think I know where we might start.

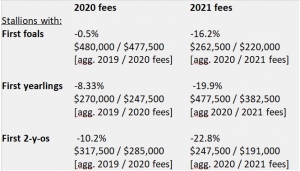

We all know that most stallions never earn a fee higher than their opening one; and that things are nowadays getting tough even for stallions entering their second year. Such is the nervousness of commercial breeders about taking a yearling to market once its sire has been exposed even to the (highly unimaginative) judgement of the sales ring; never mind about sticking around long enough to see whether the stock can actually run.

Many farms have duly sought to incentivize loyalty to new stallions. Breed your mare to such-and-such a horse for his first two years, for instance, and you can come back gratis ever after. Of course, there’s a pretty bleak inference. By the time you get free access, many stallions may have reached a point where you would rather pay to go elsewhere anyway.

The woman who contacted me this week suggested that farms might extend the logic behind such schemes precisely to those stallions who are now going “cold.” Cutting their fees, she remarked, always feels like a kick in the teeth to those who supported them the previous year. Say you paid $30,000 for the foal in your mare’s belly; and now, even before its delivery, the same sire is down to $20,000. That puts a red flag over your foal straightaway, and will hardly encourage you to double down with a return cover.

Perhaps, then, farms could play nice with my breeder by going back to her and saying: “Look, we’re sorry about devaluing your investment in our horse. You believed in him, after all–and we still do. So we’d like to invite you back. If you’re prepared to persevere with him for 2021, at his new fee of $20,000, we’ll backdate that rate to this pregnancy as well.”

The farm would only get $40,000 for two covers, instead of the $50,000 due at the prevailing rates. But that’s still a whole lot better than $30,000 for one cover, plus zilch for the next year as the disgruntled breeder seeks sanctuary in some random freshman. In theory, remember, fee cuts are only made in the hope of encouraging custom–but how often do they achieve precisely the reverse effect?

Even this kind of inventive concession might not be enough for breeders to whom any savings on fee may seem relatively marginal, relative to the depreciation invited by that red flag. But the farm, in that case, would still get to trouser its $30,000.

If farm and breeder can meet in the middle, however, the “cooling” stallion might yet be able to stay in the game a little longer; long enough, perhaps, to earn a more realistic assessment than is typically made of a single crop of juveniles, often by a stallion who only earned his place at stud by thriving with maturity round a second turn. And that, in turn, might even reduce the frequency with which farms cut their losses and sell a stallion overseas or into a regional program–which is akin to sticking that red flag right under the tail of your poor yearling.

Regardless of whether this suggestion would be practicable, or effective, the key is that stallion farms and breeders work together to break the vicious cycle devaluing the commodities traded by both. Because while their mutual arrangements ultimately only determine “supply,” both might enjoy greater security if the “demand” were better educated.

Gradually I am beginning to grasp how farms and breeders alike feel pretty helpless about the overloading of new stallions. Certainly the farm accountants would like nothing better than business balanced through the roster. As it is, everyone is at the mercy of the purchasers. Because it’s the guy sticking a hand up at ringside who really needs to put a premium on the horse bred to run, as opposed to the one produced merely to look the part on the rostrum.

There are two big problems in current purchasing behavior. One is that so much of it is driven by pinhooks: yet another commercial cycle, in other words, dividing the planning of a mating from the aspiration to win races. The other is that the professionals guiding end-users–veterinarians, agents and so on–are directing traffic to the show ponies. In some cases, okay, they simply want to avoid appearing at fault for any structural defects that may emerge later. In others, however, they are taking out a less pardonable insurance.

If they were trying to provide a real service for their patrons, they would buy or breed a horse by, for instance, the perennially under-rated Lookin At Lucky. But they don’t want to say: “Just look, sir/madam, at the fantastic value I have secured. I can only do that for you because everyone else is too dumb, or too scared, to risk walking back through the herd.” Instead they steer the action to stallion X, saying: “Don’t blame ME if this goes wrong. Because you can see the whole community of experts just loves this guy.”

And the commercial consensus can barely be dignified as “fashion,” which might at least last a year. Increasingly, they are mere fads. One of the main reasons why the big farms throw such numbers at their new sires is because a single headliner will serve as a fig leaf to the modesty of literally hundreds of other foals. A stallion’s entire career can hinge on a single member of his first crop. Horse A lands on a weak Grade I, with the right pace or track bias, and daddy is made. Horse B may be a street better, but he gets injured schooling in the gate and doesn’t run until he’s four. By then, the die is cast.

A couple of days ago we looked at the story, virtually the parable, of Daredevil–who was down to 21 mares when sold to Turkey after a quiet start by his first juveniles. Clearly, however, it’s extremely rare for such horses to leave behind an adequately stinging rebuke to earn a passage back home.

The buyers may well retort that it’s not easy to find stallions like Lookin At Lucky. Most “proven” sires are, deservedly, also expensive ones. If there just aren’t that many around who reliably get you a runner at an accessible price, then the best you can do is take a punt on a new stallion–and hope that you have stumbled across the next Constitution, or Not This Time, or whoever.

But I can’t have that. Throw the same cavalry of mares favoring the rookies at many of those slugging away at that level between The Factor and Midshipman, say, taking in your Midnight Lutes and Sky Mesas and Mizzen Masts and so on, and do you seriously think your stakes ratio would be–well, “diminished”? Apart from anything else, moreover, why not take the same gamble at slashed fees on the many Classic-oriented stallions who haven’t really had a chance to establish their merit or otherwise, in their fourth or fifth seasons at stud?

To improve supply, we have to improve demand. We shouldn’t be dragging the spenders, the guys who come to the professionals for guidance, into our fitful, fretful, flighty pursuit of the quick buck. Do the right thing by the fellows with the dough, after all, and we’ll also end up doing the right thing by the breed. And, ultimately, we’ll make the whole business more sustainable.

In Britain, where prize money is notoriously inadequate relative to the cost of participation, they strive to fill the gap with heritage and pageant and the associated prestige. By the same token, if American horsemen want to sustain investment–in training fees, especially, which keep piling up even as your gamble on a freshman sire rapidly “diminishes” through the claiming grades–then they must work, above all, at the experience of ownership.

If the whole adventure can be made glamorous and fun and compelling, something that people of all classes will want to share with their friends (and vaunt to their enemies!), whether at Saratoga or Finger Lakes, then who knows? Maybe they might want to buy actual runners, rather than throw all their money at our oil-strike fantasies about a home run in the sales ring.

The post This Side Up: If You Can Run, You Won’t Have to Hide appeared first on TDN | Thoroughbred Daily News | Horse Racing News, Results and Video | Thoroughbred Breeding and Auctions.