Last month, California Horse Racing Board (CHRB) chairman Greg Ferraro scratched a persistent industry itch.

While discussing his thoughts on the rollout of the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Act's (HISA) drug control program, Ferraro shared his fears that the new federal rules on joint injections were weaker than had previously existed in California.

“It's a step backwards,” Ferraro said. And this regulatory reshuffle, he added, could lead to an increase in California of irreparable musculoskeletal injuries, especially of the fetlock joint.

“California is the point of the spear in terms of dealing with the public and the liability of horse racing,” said Ferraro, advocating for federal adoption of California's joint injection regulations. “I think they should use us as a sort of leader in animal welfare and jockey welfare.”

Ferraro's comments re-ignited a debate that has been simmering away in some fashion or other for decades. Just take the New York Task Force report into the rash of fatalities that bedeviled Aqueduct during the winter of 2011-2012.

“The Task Force believes that the use of systemic or intra-articular corticosteroids may have impaired veterinarians and trainers in accurately assessing horses' soundness leading up to a race,” the report found.

“The Task Force also believes that the use of these medications too close to the race may have limited the ability of the NYRA veterinarians to identify the presence of pre-existing conditions disposed to progressing to catastrophic injury.”

The New York Task Force's findings frame a key bone of contention among trainers, veterinarians and regulators: What is a smart regulatory timeframe for limiting joint injections before workouts and race days?

HISA's joint injection rules bar joint injections within 14 days prior to post-time, and within seven days of an official workout.

In California prior to HISA, the intra-articular corticosteroid fetlock injection rule mandated a 30-day stand down period prior to racing, and all corticosteroid joint injections had a 10-day stand down before workouts.

After those rules were adopted, the number of irreparable fetlock injuries in California had fallen off precipitously. Experts point to this as a prime example of the long-term systemic effects from corticosteroid usage.

Even so, there remains some skepticism within the industry that California had indeed got it right.

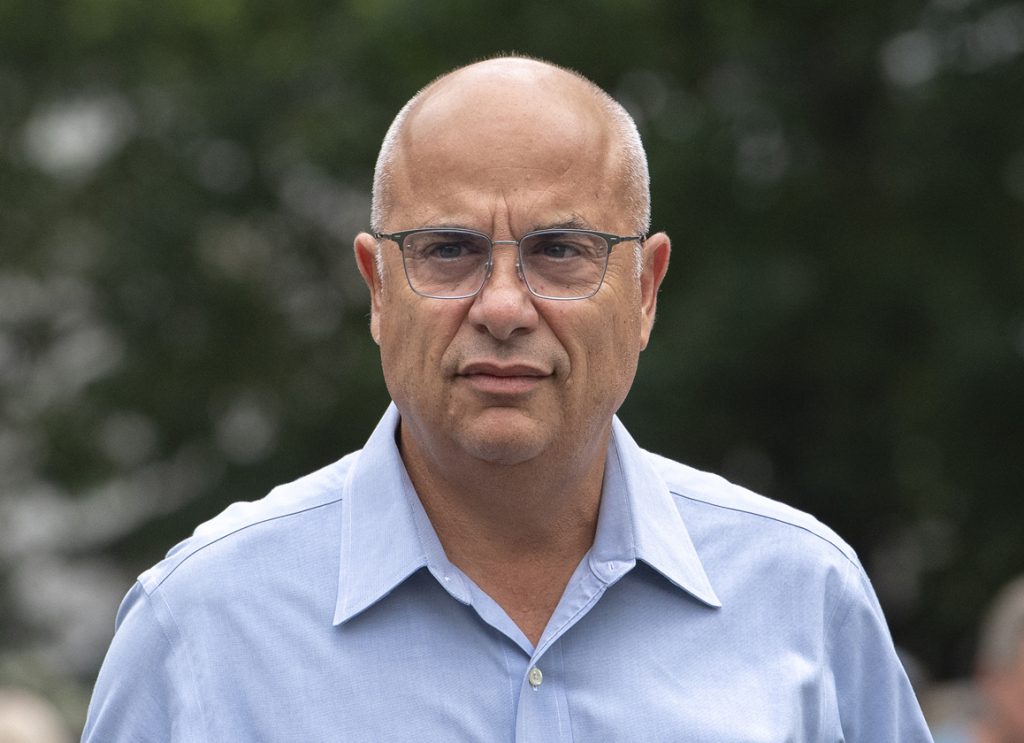

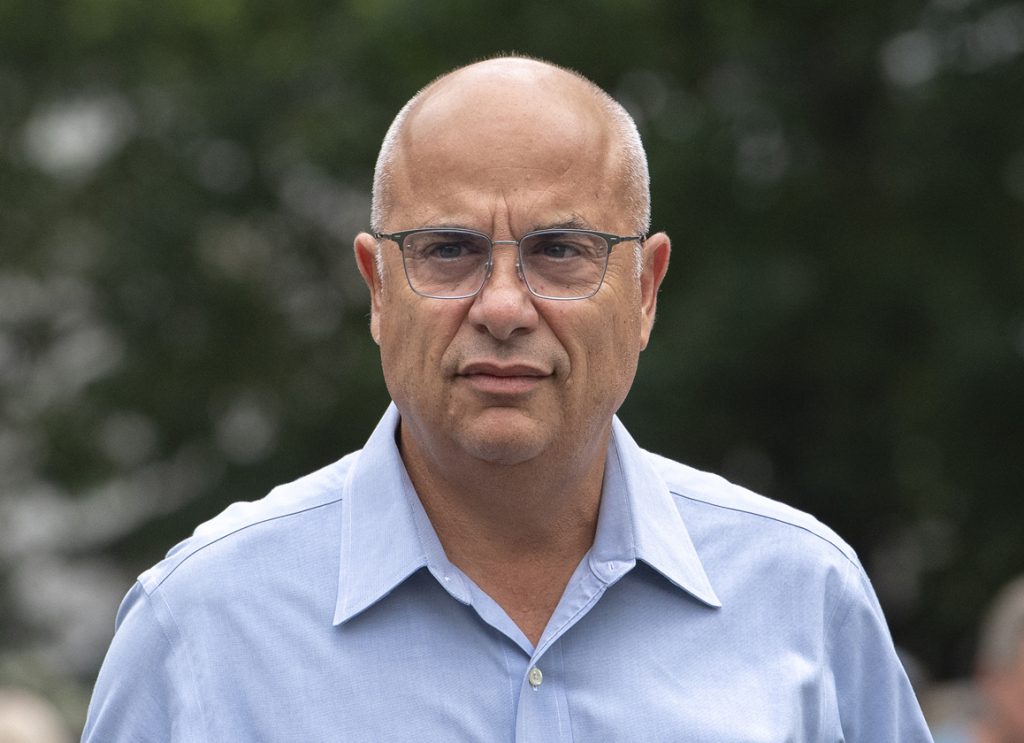

Mark Casse | Sarah Andrew

“Thirty days is ridiculous,” said trainer Mark Casse, who argues that such a rule is difficult to police. “What happens is, when you make rules that you cannot really enforce, it only makes the bad guys better because they don't care.”

Another key point in this whole debate? Not all joint injections are made equal.

In the decade since the New York report was issued, veterinary experts describe a shift away from corticosteroids towards hyaluronic acid joint injections, and biologic therapies like IRAP and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections.

They don't mask injuries the way corticosteroids can and are better at promoting joint health and healing in a way more advantageous to the horse in the long term, say proponents of these therapies.

Nevertheless, these same proponents voice frustration that the rules governing joint injections often treat corticosteroids and biologic therapies as equals.

“A lot of these injections are actually helpful, especially when you're doing PRP or you're putting [hyaluronic] acid in there,” said Casse, about biologic therapies. “I can tell you for a filly like Tepin, we would put acid in her ankles. We probably did it 20 times and she ran for years.”

Corticosteroids

Internationally renowned orthopedic surgeon Larry Bramlage is among those experts who believe HISA has got its rules surrounding corticosteroid joint injections about right.

“I think it is a good approach to being able to treat the joint that has been properly examined,” said Bramlage, who explained that corticosteroid joint injections should never be part of a “routine training program,” no matter the stand down time. “You want plenty of time to reassess the condition of the joint without the corticosteroid masking anything.”

Part of Bramlage's reasoning is how the marketplace for corticosteroids has evolved from high-dose, long-lasting versions like Methylprednisolone acetate–also called Depo-Medrol–to lower-dose, shorter acting corticosteroids like Betamethasone and Vetalog.

What kind of difference are we talking about? “We tend to think in terms of volume injected into a joint,” said Bramlage. Depo-Medrol can come in doses as strong as 40 milligrams per milliliter (mg/ml). Betamethasone, on the other hand, typically comes at a strength of 6 mg/ml.

“The original one–and as it turns out the most harmful one–was Depo-Medrol. When I was a student, we would put as much as two cc's [cubic centimeters] of Depo-Medrol when we were treating a joint,” explained Bramlage.

“But it's very long acting,” he added. “Its crystals are absorbed very slowly, so it can be found up to three months in the joint after you put it in. And that is a big disadvantage.”

Dr. Larry Bramlage | Horsephotos

Bramlage believes that the new wave of corticosteroids continues to play a role in managing the sorts of routine aches and pains that accompany high stress training programs.

“If you let inflammation go unchecked within a joint, it can eat up the articular cartilage. So just leaving a joint seriously inflamed without treating it with anything is also not the best route once you know there is no structural damage,” he said.

And the use of a low-dose, short acting corticosteroid like Betamethasone within a week of a timed workout, Bramlage said, is “a medically sound” approach if the joint has been properly assessed beforehand.

If the corticosteroid is eliminated from the horse's system enough to be undetectable in a test, he added, and the horse is still exhibiting signs of lameness, then there is a strong possibility the lameness is tied to some deeper-seated structural problem. A burgeoning stress fracture, for example, or abnormal bone remodeling. “That is the rationale for the stand down time,” he said.

The modern short-acting corticosteroids “reduce the inflammation and then get out of the way so you can read the joint again,” explained Bramlage. “And if there is a physical injury, a structural problem of some kind, it'll show up again.”

Other veterinary experts in the field have a slightly different take.

Though a corticosteroid won't necessarily show up through testing after seven days, it can still impart a systemic effect on the horse through effects like decreased inflammation in the joint and reduced lameness, said veterinarian Wayne McIlwraith, a distinguished professor at Colorado State University and like Bramlage, internationally renowned in the field.

As an example, McIlwraith cited a study he was involved in from 1997 where researchers studied the effects from triamcinolone acetonide joint injections–drugs which come under the trade names Vetalog or Kenalog. The horses were suffering osteoarthritis in the knee and were injected at 14 days and 28 days after the study start.

“We showed that lameness was significantly reduced at day 70–42 days after the second injection,” said McIlwraith. He described these effects as reduced inflammation in the joint fluid and in the joint lining membrane, as well as beneficial effects on the articular cartilage.

These effects were seen “whether we injected the osteoarthritis joint or we injected the opposite normal joint,” McIlwraith said. “In other words, a systemic effect that was very long lasting.”

McIlwraith and his fellow researchers used the same study design on Depo-Medrol–then considered the most potent corticosteroid available. They found “significant deleterious effects” to the joint cartilage in both the osteoarthritic joint and the opposite “good” joint, he said.

“The bottom line is that all the tissues of the musculoskeletal system are being exposed to the multiple complex effects of corticosteroids,” he said.

The fetlock has long been the Thoroughbred racehorse's Achilles heel. As an example, fetlock failures constituted in California nearly 60% of all musculoskeletal injuries that proved fatal during the 2018-2019 fiscal year, according to CHRB data.

The CHRB instituted its 30-day standdown regulations for corticosteroid fetlock injections on Oct. 19, 2021.

In the 20 months preceding that date, there were 83 catastrophic fetlock failures statewide, according to CHRB data. In the 19 months after that date, there were 24 catastrophic fetlock failures statewide.

Dr. Wayne McIlwraith | Colorado State University

Zeroing in specifically on Los Alamitos, the number of catastrophic fetlock failures dropped from 21 to just three during those two same periods of time bookending the rule change.

California's tightened joint injection rules have been just one part of a suite of stricter drug and equine welfare and safety rules instituted in the state over the past few years.

But for the likes of McIlwraith and Ferraro, the remarkable drop in irreparable fetlock injuries is due largely to one thing–the stricter corticosteroid joint injection regulations.

“I think we can relate this knowledge to our data in Southern California showing that injection not being allowed for 30 days in the fetlock has reduced the incidence of catastrophic injury,” said McIlwraith.

Indeed now, Ferraro advocates for the total elimination of corticosteroid use in all joints in racing and training.

“I would argue, look at our results. We didn't really have a breakdown problem with fetlock joints [in California],” said Ferraro. “In other words, if you're going the corticosteroid route, then that horse ought to be given significant time off, which means sending him to the farm.

“You can't legislate good judgment,” he added. “Corticosteroids in the hands of a wise, experienced equine veterinarian, you could probably do fine with it. But we put in this legislation because we know good judgment is not something that's always [wielded on the] backside.”

Which leads to alternative therapies to corticosteroids.

Biologic Therapies

“What you're trying to do is either slow something down or speed up something, and the goal is to slow the bad stuff down and speed up the good stuff,” said Bramlage, of the role of veterinary intervention with biologics. “[They] don't work by stopping things. They try to augment healing, not only block the mediators of inflammation.”

In explanation, Bramlage pointed to how the joint protects itself from harm and degeneration by naturally producing hyaluronic acid in the joint fluid, along with a class of molecularly heavy proteins called proteoglycan in the cartilage.

White Abarrio | Coady Photography

But corticosteroids hinder the body from producing both hyaluronic acid and proteoglycans. As such, hyaluronic acid is frequently used in combination with corticosteroid joint injections.

“You're essentially artificially adding hyaluronic acid because the corticosteroids are going to slow or stop the manufacturer of hyaluronic acid in the joint when you put them in,” Bramlage said.

When it comes to the use and efficacy of biologic treatments on racehorses, there seems to be a broad and largely favorable consensus among veterinary experts.

“You get your results from them because they stimulate healing within the joint. They calm the membrane down, and they help the cartilage surfaces. In other words, you could say they're a form of nutrient for cartilage, whereas steroids are a toxin to cartilage,” said Ferraro.

Should biologic therapies and corticosteroids joint injections be treated the same by regulators?

“No,” said McIlwraith. He explained that through research and through widespread clinical use, these therapies have been shown to have “uniquely beneficial” and other specific effects, but “no significant” negative effects.

“They are less potent immediately compared to corticosteroids which means that they are not going to be useful if used in an 'inject and race or work soon after' manner, which has been a philosophy of use by some,” said McIlwraith.

But under HISA's current rules, all joint injections are indeed treated the same. This means that biologic treatments like IRAP and PRP injections require the same 14 and seven-day standdowns for races and workouts respectively as corticosteroids.

HIWU has suspended 40 horses from racing for 30 days due to joint injections within seven days of a timed workout. Equibase only publicly maintains 60-days' worth of workout data. With what information is still available through Equibase, at least one horse on the list was injected one day before a workout. But HIWU does not publicly detail what kinds of joint injections were administered to these horses–corticosteroids or biologic treatments.

Efforts are underway to potentially modify HISA's joint injection rules.

A red-lined version of HISA's ADMC program recently shared with the TDN prohibits horses administered a fetlock joint injection from racing for 30 days, and from working for 14 days. For all joints other than the fetlock, the current restrictions–14 days from racing, seven days from working–remain in place.

According to this red-lined version, the rules still don't differentiate between corticosteroids and biologic therapies.

CHRB equine medical director Jeff Blea sits on HISA's anti-doping and medication control (ADMC) committee.

Though Blea was speaking on behalf of HISA, he said his personal opinion was that the federal ADMC program should be altered to mirror California's rules, which allow biologic therapies to be used unrestricted on any joint before a workout.

“We should want to be promoting biologic therapies because I think it's beneficial not only in the short term but the long term,” he said.

At the same time, not all veterinary practitioners agree with all aspects of the CHRB's rules on joint injections. If a horse is injected three times into the same joint within 60 days in California, the horse is automatically placed on the vet's list for 30 days.

This rule went into effect in the state on July 1 this year. And it has curbed Southern California veterinarian Ryan Carpenter's use of biologics, as it fails to distinguish between those sorts of injections and corticosteroids.

Dr. Jeff Bleu | AAEP

“It essentially has eliminated our use of IRAP, which is designed to be done once a week for a loading dose and then monthly after that,” said Carpenter.

“The unfortunate thing is that rule has actually incentivized people to not use biologics and put them back towards corticosteroids,” said Carpenter. “My corticosteroid use has increased since that rule has come in effect and would have loved to have stayed on the biologic route because I think it's better overall.”

When asked about this criticism, CHRB executive director Scott Chaney argued that the 60-day period was specifically chosen to still permit the use of biologic therapies while curbing excessive injections into the same joint.

“Even if it's not degrading the joint, clearly it's not working if you're having to mess with a specific intra-articular space over and over again within a short timeframe,” Chaney said.

More broadly, Chaney's thoughts about corticosteroid use in racing align with Ferraro's.

“Corticosteroids are unnecessary in horseracing,” he said, calling this issue a “litmus test” for HISA. “Our horsemen in California have been there and done it. We're four years into this,” he said.

“But it seems like horsemen around the rest of the country need a 'come to Jesus' moment because they're still clinging to the belief that they need corticosteroids to work a horse or run a horse. That's absurd. Any horseman or veterinarian who tells you that, they do not know what they're talking about.”

`I Would Put This Stuff In The Water'

It turns out the evolution in the use of joint injections in human athletes—and aging athletes in particular—appears remarkably similar to that of the racing world.

Andrew Pearle is the Chief of Sports Medicine at the Hospital for Special Surgery, the country's top orthopedic hospital. He is also a team physician for the New York Mets.

Pearle's area of expertise? The human knee.

“When I'm giving a steroid injection, I typically give 80 milligrams of Kenalog. It's a really good injection, particularly if there's fluid on the knee. It's certainly highly effective. In fact, there was a Nobel Prize given for the development of cortisone,” he said.

But there's a caveat.

“It's got these downstream negative effects with repeated use, and many of us don't like to give more than two shots over a lifetime in a joint,” Pearle said.

Instead, said Pearle, human medicine had moved towards alternative joint therapies like gel shots, PRP and hyaluronic acid.

“I tell patients if I could put this stuff in the water and feed it to everybody,” he said, “I would.”

The post Joint Injections: “Litmus Test” for HISA appeared first on TDN | Thoroughbred Daily News | Horse Racing News, Results and Video | Thoroughbred Breeding and Auctions.

Source of original post