In this TDN series, we curry lessons and wise counsel from veteran Californian figures who, like gold nuggets panned from the Tuolumne River in the High Sierras, have unearthed career riches on arguably the toughest circuit in the States.

The series started with John Shirreffs and Art Sherman, and continues here with Eddie Truman, who announced his retirement last month.

The land around Mulvane, Kansas, has been flattened as though by some colossal steamroller, and the vast, leafy battalions of maize and wheat and sorghum stretch outwards on and on until the horizon appears to meet another universe entirely.

“Imagine what's out here,” it seems to say (this is the Bible Belt after all). “Go on, take a look.” But before you do, it's best to go equipped with a few basic life lessons.

“I don't know who taught my dad or how he figured it out or what, but we would re-break horses from these other farms around us. Everybody else would get a horse and then ruin them,” said Eddie Truman, when asked where the foundation stones of his long training career were cemented.

He then laid out a formula for how the Truman family successfully rehabilitated those four-legged delinquents on their little Kansas farm. These would have been the years of chrome fenders, subway vents straddled by platinum blonds, and the distant shadow of “Ike” Eisenhower.

“We had a small corral and we would start totally over with them all. We would start lunging then driving them,” said Truman. “By the time we got on them, they were responding to the bit, and he [dad] taught us that you correct them hard and fast, but then let them go and say, 'hey, we'll give you another chance.'

“We didn't buck-break them out or anything like that. This is where dad had the edge–our horses never bucked. No. As soon as we got them out of the pen, we'd take them out in a plowed field. It was deep stuff, so they couldn't do too much. But it really taught us, all of us, to be kind, gentle hands, and to let horses relax–correct them, but then give them a chance. It was good.”

Good for horse. Good for rider. “We learned some really valuable horsemanship that way,” said Truman.

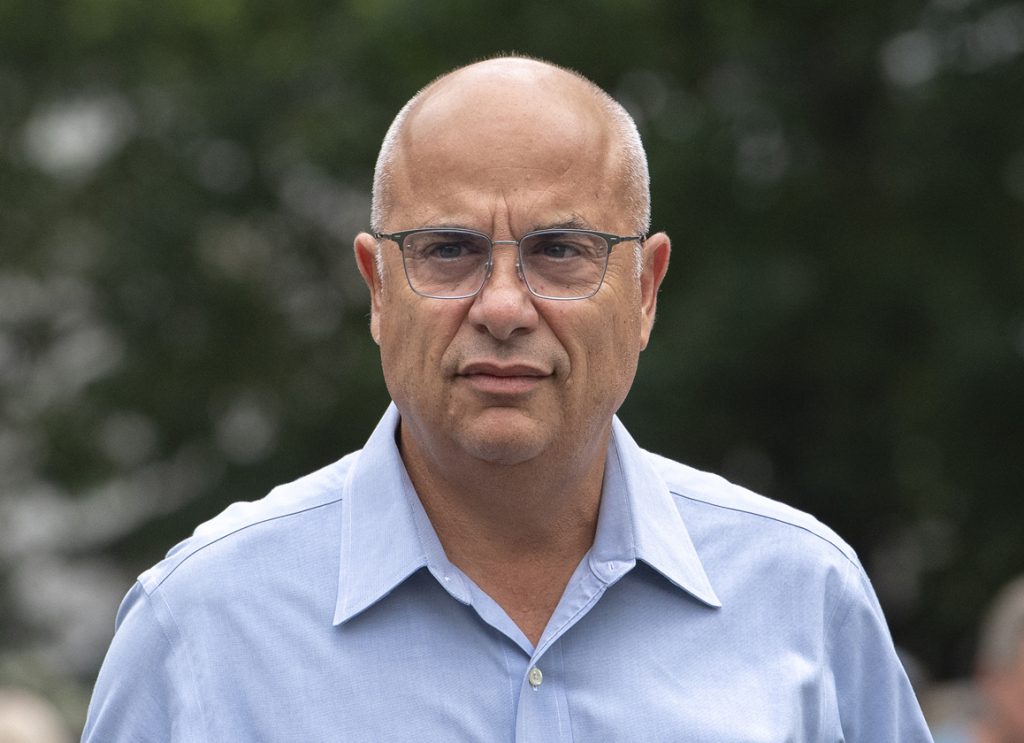

In a neatly ironed plaid shirt and navy-blue jeans, the recently retired trainer cut a relaxed silhouette on a warm early February morning outside the Starbucks in Sierra Madre, a sedate little town just north of Santa Anita, where the treasure lies in the view itself–the painterly backdrop provided by the San Gabriel Mountains that could have been stolen from the set of a John Huston spaghetti Western.

If Mulvane opens out, Sierra Madre leans in. One place easy to leave, the other easier to stay. And Truman has lived in and around Sierra Madre since the 1970s.

At 77, he's as wirily trim as a bantamweight boxer. Thank a lifetime in the saddle–peddle-bike and horse–for that, amid a near 50-year training career defined not so much by the usual barometers of success (Kentucky Derby garland, a laundry list of graded stakes wins), as by a more indeterminate metric, and one that, as a result, is perhaps more readily brushed aside. Especially in an age that covets above all else the religion of certainty.

Sure, he's trained plenty of winners–763 of them, to be exact. “But to see a horse get good and see them just develop, get confidence, that was really fantastic to me–more so than even having a real nice horse that just goes out there and wins every time or runs hard every time,” said Truman, acknowledging what many regard a strength of his approach to training–the prospector's gift for panning gold from grit.

“Maybe they weren't great horses, but they would go out there and perform for you.”

Indeed, two of Truman's most accomplished works are horses that joined him half-made. Go West Marie had shown just fair form on the East Coast before joining the Truman stable halfway through 2014. Under his watch, the daughter of Western Fame won four stakes races and was just a length away from winning the 2015 GIII Las Cienegas S.

He got the best out of Fairy King's son, Casino King, an Irish import who showed up time after time in some ferocious bouts on the turf, including a clear second behind triple Grade I winner Bienamado (Bien Bien) one June at Hollywood Park, a second-place finish in a Grade II at Woodbine and a stakes victory at Remington Park.

But those wayward types, they were the ones Truman really got a tune out of. “I would not actually search them out,” he explained. “But if I liked their form and I saw they were like that, I figured they could be better. Yeah. That would be one thing that I didn't mind at all.

“A lot of times the reason horses are acting up or not performing is because they're hurting. That's a lot of it–something's wrong,” Truman added. “You need to get them happy. Try to get them sound and get them happy again. And then just patience. Patience with horses I think comes down to mainly repetition.”

Ah yes, repetition–10,000 hours of it to make a genius, or so says Malcolm Gladwell.

To illustrate, Truman recalled how one of his last trainees arrived with a pre-existing phobia, one especially ill-suited to the low-drooping lids of Santa Anita's backstretch barns.

“They couldn't get her under the shedrow. She didn't want to go in the stall–she was scared of it,” he explained, cutting a cross with a hand. “Nope.”

Carefully, persistently, Truman and his team successfully weaned the filly from her neurosis.

“After about three weeks, she's going in pretty good. And after about a month, month and a half, she's like a normal horse walking in,” said Truman. “It just shows that time and patience are the key to horsemanship.”

True to his days on the Mulvane flats, Truman preferred to meet challenges posed by his equine Rubik's Cubes hands-on. That he was an accomplished rider didn't hurt. Even into his sixties, Truman could be seen of a morning bobbing on horseback around Del Mar and Santa Anita (sometimes in shorts, to the consternation of anyone with skin on their knees).

Truman's racing teeth were cut out on the dusty country roads of Kansas and Oklahoma, back then the epicenter of Quarter Horse match racing. As it was being laid out, Interstate 35, which cut a slice up through the spine of the country, proved a useful trial-ground.

“I'm getting on these Quarter Horses and they're flipping over, rearing up in the gate. I'm 11 years old. I weighed like 80 pounds or something, 85 pounds wet through. Oh, man–it was years before I was real comfortable in the gate.

“When you think about kids now, they would've locked up our parents. They would have hauled them away in handcuffs. But hey, that's the way it was.”

Truman rode his first winner aged 12, on a Thoroughbred going half a mile. At 16, he followed into the professional ranks his brother, Jerry, already an established jockey. Truman was contracted to the owner of the Chicago Blackhawks.

“They were kind of a gambling outfit, but [trainer] Paul [Kelly] was really a good horseman, very well respected.”

So much so, Truman was leading rider one year at Sportsman's Park.

When the scales became too much of an enemy, he took a year or two jumping from role to role–exercise rider, veterinarian's assistant, patrol judge–to eventually becoming private trainer to an owner called David Kelly in Detroit [no relation to Paul].

“I knew basic horsemanship and being a jockey and understanding the fitness of a horse, the way he's traveling. I was pretty good at that. But still, I hadn't really paid that much attention to the legs before then. I didn't really have the whole thing about training down pat. But I did take really good care of my horses.”

Less than a year in, Kelly's business empire went belly up. Truman was cut loose once more, flinging open the doors to what proved his “Eat, Pray, Love” years. He headed to Europe with little itinerary and even less luggage.

“I was just bumming around, traveling all over, just trying to decide what I wanted to do,” said Truman.

Six months later he was back in the States, headed west to Bay Meadows for a paddock judge position, then south to Santa Anita, exercise riding for a claiming trainer making his name as an unusually astute conditioner of the Thoroughbred racehorse.

“Most of the time it would be all about less,” said Truman, when asked what abiding lessons he took from his time working for Hall of Famer Bobby Frankel.

“Most of the time we'd just jog them. Pretty simple. That's what I often did, too, as a trainer,” Truman added. “Though I maybe carried that too far. I was too conservative sometimes. But he just kind of knew where horses were at, and which horses to go on with more.

“We had some horses you'd think were pretty sore. He'd say, 'go work him.' I would say, 'man, Bobby.' But he just knew. 'Don't worry about it. Go ahead.' And nine times out of 10, it would work out. But I was always scared to death to do that.”

Given the stock in the Frankel barn at the time, it figures that the old racing adage, “keep yourself in the best possible company and your horses in the worst,” was another useful tool that Truman took with him when he eventually set up on his own.

“When I started, we got lucky. We claimed a horse that won like six out of nine races. Claimed another one that won four out of five. We would run them where they belonged. Run them up north,” said Truman.

“That was one of my favorite games: Claim a horse here [Santa Anita, Hollywood Park] while they were in jail, run them up north, win, come back here, run them for what I claimed them for–I'd already won a race with them–and go on. You build up their confidence. Confidence–it's a big thing. People don't understand that.

“Around the barn the next day–maybe the horse gets it from the people being happy, who knows–but that horse is different when he wins than when he loses. He's different. He has more confidence. He might be tired, but he's stronger. And man, get him to win a couple races, they're tough. They'll lay their body back for you. You run a horse over its head too many times, it doesn't matter where you put them, they run just the same.”

Training, of course, is anything but a solitary pursuit. Just as it takes a village to raise a child, it would take a census to count the number of hands that have touched, brushed, ridden, prodded, picked and shod any horse along its route to the winner's circle.

Frankel, it seems, had particular ideas about what that village should resemble. So does his protege.

“If [Frankel] saw a groom wasn't handling a horse a certain way, I think he'd be more inclined just to get rid of the groom instead of taking the horse away from him,” said Truman.

“I kept one old guy with me for about 25 years,” Truman added. “He'd fight with everybody. Cranky? Oh, man. He'd want to get his horses out first. He'd get up at 2:30 in the morning. We'd start at six. Oh man, what a pain. But he loved his horses. Loved his horses. A good horseman. That's a big deal.”

Truman wears the cheerful veneer of your friendly neighborhood postman. He tosses the phrase “oh, man” into the conversation like a frisbee. Breezy optimism suggests he's figured out the pursuit of happiness. But all this personability hides an examining mind–one clearly not shy of turning inwards.

Truman admits he's glad he's not starting out a trainer in today's racing ecosystem. For one, he said, the era of the super trainer has led to the lopsided distribution of horses concentrated among fewer and fewer hands. Good horses especially.

“When I came out here, every barn you walked under, it didn't matter if they had six horses, they had 12 horses, they had 32 horses, every barn had a big horse. Every barn. And that's what I'm talking about when I talk about the distribution. Every barn had a big horse. And now here we are,” said Truman, arguing that California should reinstitute the 32-stall limit per-trainer at each licensed racetrack.

“I really think it's ruined racing,” he said. “I think it hurts everybody.”

He also sees the multi-faceted roles of a modern trainer–data analyst, PR guru, TV personality, navigator of bureaucracies–as an evolution that takes the job further and further away from its core tenets of horsemanship and animal husbandry.

“If you're a trainer, you might have a problem if you don't have a college education,” he said. “Why is that? You need to talk to these people, the owners, the media. You need to post stuff, take pictures of the horses, send them videos of workouts. And so, I think the game's changed. It's definitely evolved into one more focused on the owners, so that the training of the horses is secondary.

“Another thing that I learned later on is that all this stuff we do is meaningless if the horse isn't able to run,” Truman added. “Maybe the odd horse, you can do this or that a little different. But hey, everybody's feeding the same. They're basically training about the same. The horse has got to be able to run. And so don't worry about all this other stuff.”

In stripping the game of some of its starry romanticism, Truman lays out a case for balancing his professional and personal lives, not letting the two intermingle. No social gatherings at the barn. No long evening fireside chats on the telephone, all shop talk with the owners. No busman's holidays, families in tow.

“Charlie [Whittingham]'s favorite saying was, 'owners are like mushrooms. Just feed them shit and keep them in the dark.' But Bobby was the opposite. He would say, 'don't come to the barn, I don't want to talk to you. Don't bother me. I'll see you at the races,'” said Truman, who said his approach hued closer to his old mentor's.

“I didn't want people bothering me at night either–I wanted to spend time with my family. So that's what I chose–that's the road I chose. I said, 'I'm going to enjoy spending time with my daughter and my family. Put my life first and the horses second.' That's the choice I made.”

Does he regret that approach now?

“Hey, I would have loved to have had a horse for the Derby and this and that. But again, that was my own fault, too. I didn't capitalize on the communication with people, with owners.”

Truman recalled the time Ed Friendly, a heavy-hitting California owner-breeder, approached a mutual friend with the offer of sending a squad of horses Truman's way.

“I gave him my phone number,” Truman recalled. “[Friendly] says, 'now, is this your home number?' I said, 'no, I don't give out my home number. I don't want anybody to call me at night.'”

Friendly was unimpressed.

“He told my friend afterwards, 'who does he think he is? I'm going to give him some horses and he doesn't want me calling him?'”

The Friendly horses remained strangers.

As the hot February sun reached its midday zenith, the conversation turned to the legacies of long-passed California trainers–names, institutions that pepper the history books and old Daily Racing Forms, but have slipped from our everyday lexicon, lost amongst the detritus of lives lived in haste.

“I wonder, if you were to walk out here today and ask most of the trainers who Charlie Whittingham is, how many would have a clue? I think they would say, 'oh yeah, he used to be a trainer.' But how many would know why he was a good trainer?” Truman asked, before listing other dusty names. Buster Millerick. Robert “Red” McDaniel.

“Now go out there and see if they know who they are.”

Truman paused, interrupted by passers-by who recognized him, wished him well in his retirement. When they strolled on, Truman quietly gathered his thoughts.

“You never know if it would've worked out anyway,” he said, eventually, still lingering on past chances. “But I wanted to spend time with my family. So, that's the road I chose,” he added. “And I never really regretted my choice that way.”

The post Eddie Truman: No Regrets on the Road He Chose appeared first on TDN | Thoroughbred Daily News | Horse Racing News, Results and Video | Thoroughbred Breeding and Auctions.