Some kind of wand has been waved here. Of eight starters in the GI Preakness S., three represent the first crop of Good Magic–including GI Kentucky Derby winner Mage. Just weeks after their program received what felt like the ultimate accolade, in Broodmare of the Year honors for Dreaming Of Julia (A.P. Indy), Barbara Banke and her Stonestreet team duly have still further cause for gratification. Because just like Dreaming Of Julia, Good Magic is out of a daughter of one of the foundation mares bought by Banke's late husband, Jess Jackson.

Moreover, both Good Magic and the two, star daughters of Dreaming Of Julia are by Curlin, the dual Horse of the Year co-owned by Jackson. And while Good Magic was sold as a $1 million yearling, Stonestreet immediately retrieved a stake and could accordingly celebrate his rise as a racetrack champion and now, in partnership with John Sikura, as an overnight success alongside his sire at Hill 'n' Dale.

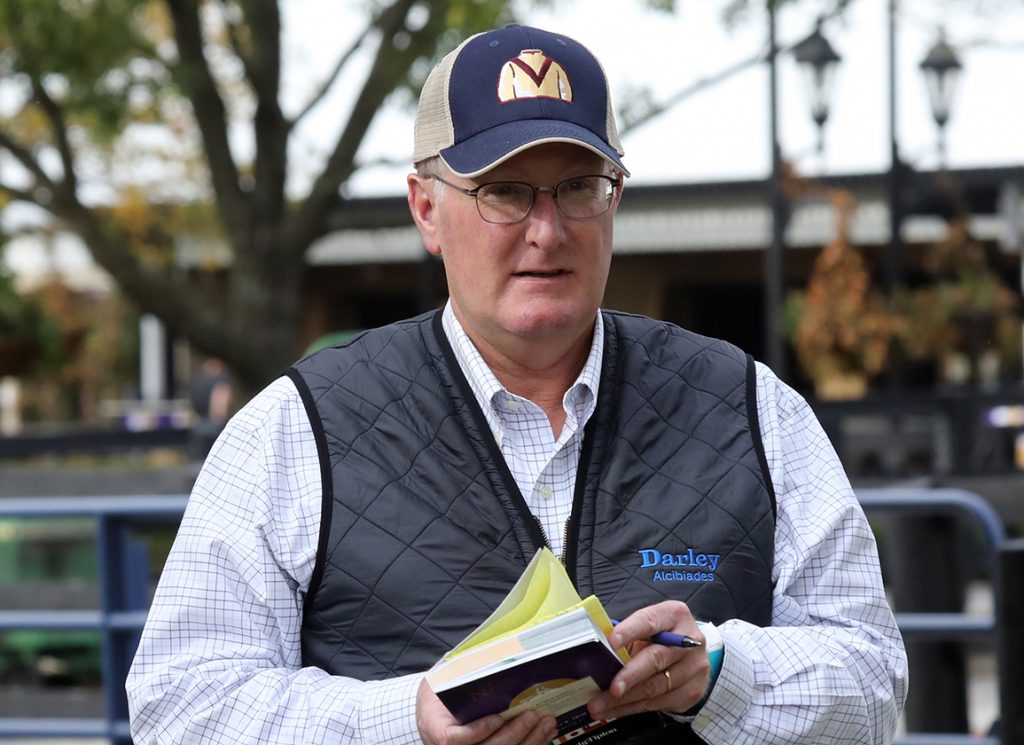

It's been a fulfilling experience for all concerned, then, not least Stonestreet's bloodstock adviser John Moynihan–who came on board 18 years ago precisely on the premise that the project would share the same spirit of patient cultivation that had underpinned Jackson's success as a vintner. For just as a long journey divides the planting of a vineyard from the savoring of the wine, so with the sowing of these recent triumphs.

Nowadays, true, no such patience tends to be offered in the commercial judgement of new stallions. If the first sample of grapes don't measure up, they tend to be left to wither on the vine. Yet Good Magic, who had himself confounded the slow-burning Curlin stereotype as a champion juvenile, not only finished second in the freshman championship but is now consolidating with his maturing sophomores. Mage himself, remember, emulated his sire's Derby nemesis Justify in winning the Derby despite not having raced at two.

Good Magic broke the mold along with his maiden in the GI Breeders' Cup Juvenile.

“Obviously, we'd had a lot of Curlins up to that point,” Moynihan recalls. “And the unique thing about Good Magic was that he was always extremely precocious. A lot of Curlins get better as they mature. But he already looked special at the training center, before we ever sent him to Chad [Brown]. He acted like he was going to be an extremely early horse, to the point where I thought he would start much earlier than he eventually did, in Saratoga.

“So, he was an anomaly that way, but he was also like so many other Curlins that you know will get even better the next year. Had he not run into Justify, we'd have had a Kentucky Derby winner and probably a Preakness winner too.”

To that school of thought, Good Magic has unfinished business at Pimlico on Saturday, in that he probably paid for squaring up so boldly to the Triple Crown winner, just run out of the places in the last strides.

“So, it feels kind of redeeming that he's turning out to be as good a stallion as he has,” Moynihan says. “We obviously bred a lot of nice mares to him, that first crop. And when the foals start hitting the ground, they looked just like he had: medium-sized, precocious-looking horses. And that's how they ran last year, too. But just as he went on to be a very good 3-year-old, so they're now making the same jump. And when a horse does that, in my eyes, they're usually on the road to becoming a very good stallion.”

One neat touch about Good Magic is that he's out of a Glinda the Good, a stakes-winning daughter of Curlin's hard-knocking rival Hard Spun.

“The two horses he kept running against were Street Sense and Hard Spun,” Moynihan reminds us. “And we had a ton of respect for Hard Spun, because he usually set the pace in all those races. Mr. Jackson really wanted to breed to that horse, and Good Magic is the culmination of that. Obviously, we love Curlin and now that he's getting older, to have one of his sons showing so much promise is a huge blessing.”

Glinda the Good's Curlin colt was always so highly regarded that prospectors at the 2016 Keeneland September Sale were advised that the vendors would be eager to retain a significant stake.

“We had put the word out,” confirms Moynihan. “And we talked with Bob Edwards [of E Five Racing] beforehand–we break horses for him at the training center–and said how much we liked the horse and would want to stay in. So, a deal was struck.”

As it happens, Glinda the Good's dam Magical Flash (Miswaki) marginally predates Moynihan's arrival, Jackson having included her among a bunch of mares acquired to support his first stud venture, Saarland. But a rather more focused agenda resulted in Dreaming Of Julia, who has made a remarkable start to her breeding career from just three named foals of racing age.

The first, a daughter of Medaglia d'Oro, was apparently sensational in pre-training but was lost in a starting gate accident. The other two (both, as noted, by Curlin) redressed that tragedy last year as GI Breeders' Cup Distaff winner Malathaat and GII Demoiselle S. scorer Julia Shining.

Dreaming Of Julia's dam Dream Rush (Wild Rush) had been top of Moynihan's list at Fasig-Tipton in November 2007, having won two Grade I sprints as a sophomore that summer, but the white flag had to be raised at $3.3 million. A couple of years later, however, her purchaser contacted Moynihan and asked whether they were still interested in the mare. Unbelievably, they had just bred her to A.P. Indy–which is just what Stonestreet had planned to do. And the result was Dreaming Of Julia, who won the GI Frizette S.

“You know, Dream Rush had a very light page,” Moynihan admits. “But she could fly. And we thought that if you bred a mare that fast to A.P. Indy, you could get a fast horse, you could also get a Classic horse.”

And from those days onwards, Stonestreet has put a distinctive hallmark on the breed: cycling back to a genetic core, whether cultivated or grafted, while admitting judicious transfusions of external blood and funds. (Malathaat, remember, made $1.05 million as a yearling and Shadwell, another elite program now assisting the family, have chosen Into Mischief for her first cover.)

“Broodmare of the Year felt like a huge accomplishment for us,” Moynihan says. “For an operation such as ours, that takes so much pride in doing things from the ground up, it's the pinnacle. I mean, her mother may have been the fourth or fifth mare that we bought.”

While Stonestreet must also trade, selling 80 to 90 percent of its yearling crop, even to maintain a breed-to-race core demands vision and courage.

“First time I ever met Mr. Jackson, he laid out was what his ambitions were,” Moynihan says. “Breeding to race on any kind of scale was in a massive decline in America. Still is. You just don't have the Mellons, the Phippses, the real sportsmen anymore. But Jess and Barbara had always been creators, in their wine business: they owned the land, they grew the grapes, the whole thing was vertically integrated.”

And that, to Moynihan, was key. He had found subsequent Derby winner Charismatic (Summer Squall) as a weanling for his first big clients, Robert and Beverly Lewis, but they were scaling down with the advancing years. Nor had they been quite so engaged by the breeding side anyway. Thinking on this kind of scale, then, was just what he wanted to hear.

“There's a lot of people out there buying yearlings,” Moynihan remarks. “They buy the yearling, the guy races his horse, they lose track. I've always been part of a program. You buy a weanling or yearling, and you manage that horse through its entire racing life, potentially its breeding life, and you see the fruits of a cyclical process. So, I'm always more interested in building something.”

As it was, Jackson and Banke brought him out to California, to the vineyards, and he saw for himself that these people would do things properly.

“Mr. Jackson knew, starting off, that we had to work our way up to what he'd call a critical mass of horses,” Moynihan recalls. “He showed me his wine operation, and I saw the best of practices within that, and the scale and the scope of what he did. But it's never just scale. A lot of people in the horse business have been big, but they haven't necessarily been great. But I saw straightaway that here was a person who was extremely passionate; and that a lot of his ideas lined up with the way I'd want to do things. And I thought, 'Well, here's an amazing opportunity to create something really great.'”

By the time he passed, in 2011, Jackson had been party to three consecutive Horse of the Year campaigns: Curlin in 2007 and 2008, and then Rachel Alexandra (Medaglia d'Oro). But it's this longer harvest that Moynihan feels would most please his late patron.

“He always said that one day we should be in a position where we can potentially produce better horses than we can buy on the marketplace,” he says. “And every year now, when we go to the yearling sales and see what's out there to purchase, a lot of times we end up saying, 'Well, we're not going to buy Hip 354 because we already have two of those.'”

That said, it's important that you also sell elite stock; that the market won't suspect you of holding back the cream. So, while two retained filles, Clairiere (Curlin) and Pauline's Pearl (Tapit), made it to the GI Kentucky Oaks in 2022-and have both since become Grade I winners-they could not beat Malathaat.

“No, you absolutely want that, for the people that buy them,” Moynihan emphasizes. “Apart from anything else, you sell the good ones because they tend to bring the most capital. If you think a yearling like Malathaat can bring a million, well, you know what, that's a lot of money. That's one horse doing a lot to fund the program.”

Obviously, we can't expect Moynihan to share too much methodology, but he plainly views racetrack excellence as evidence of a functional pedigree.

“The foundation here in America is speed,” he says. “And races like the Test and the Prioress, those are so difficult to win. Winning them made Dream Rush the fastest of her generation. And from what I've experienced, that brilliance a lot of times gets passed down to the offspring.

“A lot of people have bought unraced mares with amazing pedigrees and done extremely well, but for me that's somewhat unfamiliar. I've been much more of a results person. If I see a filly go break her maiden by 10, and something happened with her and there's no stakes on the page, I know she had brilliance and that's what interests me.”

But affinity of pedigree emphatically enters the mating equation–where another vital piece of the armory is Moynihan's familiarity, through scouting the sales so thoroughly, with the trademark traits of every stallion.

“We take everything into consideration,” Moynihan says. “Everything. It's like we put it all in a box, shake it up, pour it out, and find what gives us the best chance of producing a great racehorse. When we're doing matings, it's eight hours a day for 20, 30 days, locked in a room. And then you finally think yes, this is really going to work–only to come back and critique it maybe five more times before it gets finalized. A tremendous amount of intellectual property goes into mating a Stonestreet mare. That's not to say that it's always going to come out right. But when it does, with a great physical that we can either run or sell, then you feel like all the hard work has paid off; that the model works.”

It's a long road from the computer science degree taken by a young fellow from Frankfort, with a single strand to draw him into the horse business: Ryan Mahan, senior auctioneer at Keeneland, was a family friend. By stages Moynihan became intrigued, immersed. He read the trade press and figured: “You know what, with the securities business, you don't really have any control. But if you learn this business the right way, potentially you could have control.”

One decisive boon, on graduating to a first job at Fasig-Tipton, was being sent to spend time at Belmont Park. “You can't learn about racehorses at a yearling sale,” he was told. “You need to go to the track, look at the finished product. Go look at the sprinters in the Vanderbilt. Look at the two-turn horses in the Jockey Club Gold Cup. The 2-year-olds in the Spinaway, the Hopeful. Then come back to the unproven marketplace, and see what you should be trying to replicate.”

There was also some cherished mentorship from Johnny Jones at Walmac, before Moynihan landed running in his solo career with Lewis.

“I've been so blessed,” he says. “I've had amazing clients that have stuck with me through thick and thin. Bob gave me freedom to see the big picture. That way I really learned the business of procuring and racing a great colt, and coming full circle by being able to sell him to a stallion farm.”

An exciting new cycle for Stonestreet may have begun in the stunning Keeneland debut of American Rascal–yet another Curlin, and the first foal out of the brilliant Lady Aurelia (Scat Daddy).

“But it's such a finite number of these horses that get to the promised land,” Moynihan reflects. “Today, let's face it, everyone is after three or four stallion prospects [in each crop]. There's just a handful of races you have to win if you're trying to make a stallion. Luckily that's just what Good Magic did. But it's very hard to procure those horses today, because besides needing the racing luck, you're also going up against guys that might be spending $50 million on 120 yearlings.”

Moynihan emphasizes the contribution of Sikura to Good Magic. “He's done an amazing job with our stallions,” Moynihan says. “A lot of people think that we just stand our horses there. That's not the way it evolved. John put up his money and bought these horses, whether it be Charlatan off two races, or Maclean's Music off one.

Maclean's Music | Lee Thomas

“The only reason Maclean's Music is a stallion at all is John Sikura. I think a lot of stallion farms look at a resumé and say, 'Well, yeah, we can make money if we stand him for this fee and get paid out two or three years.' I don't think that's his model. I think he wants brilliance. The horses he has on that farm, they're there for a reason. Right or wrong, he believes in those horses and he's willing to put forth that passion to turn them into successful stallions.”

However big the business might become, then, it's nothing without that human spark. And that, evidently, has been no less essential to the evolution of the Stonestreet program under Banke, in the 12 years since the loss of her husband.

“It was always his passion, but Barbara became extremely interested with a horse called Curlin,” says Moynihan. “And when Mr. Jackson passed away, I think she wanted to continue his dream and see what we could accomplish. All credit to Barbara, if she's in town and we're foaling mares, she's there for the foaling. She's not saying, 'Hey, what kind of foal was it?' She's there. I mean, she really cares.

“When some of these things happen, I think all of us ask ourselves: 'How would he feel today?' And I think he would be over the moon, I really do. Because it's exactly what he set out to do. There are so many wealthy people that buy or breed horses: they're in wine, they're in real estate, they're in auto parts, they're a Sheikh from the Middle East. And a lot of them never have any luck. It doesn't necessarily matter how much money you have. It's how you spend it, and how you manage the horses. And so many of these processes were all Mr. Jackson's vision. I'm sure he looks down today and is very proud of what he created.”

The post Stonestreet Team Hoping For Some Good Magic In The Preakness appeared first on TDN | Thoroughbred Daily News | Horse Racing News, Results and Video | Thoroughbred Breeding and Auctions.