“It's been fun living.”—Colonel Jack Pendleton Chinn in a Feb. 14, 1902 article in the Fort Smith (Arkansas) Times

About 30 miles southwest of Lexington, somewhat sequestered from Central Kentucky's Thoroughbred epicenter, G. Watts Humphrey Jr.'s Shawnee Farm sits on a strip of velvety bluegrass near Harrodsburg in a kind of splendid cocoon of time.

The farm is very old, dating back to the era before Kentucky's 1792 founding when some of the earliest racing and breeding was taking root near the pioneer Fort Harrod, the oldest permanent settlement west of the Allegheny Mountains, which lies five miles away.

For more than two centuries, mares and foals have browsed and feasted on the farm's enlivening pastureland watered by the gentle Shawnee Run stream. Its 1,000 acres in Mercer County are partitioned by miles of distinctive green wood plank fencing atop a limestone plateau that eventually descends through thick, wooded ravines to the Kentucky River and spectacular rock palisades.

Despite the surrounding wilds and distance from the core of Thoroughbred farms northward up U.S. 68 toward Woodford, Fayette, Scott and Bourbon counties, Shawnee Farm is the very essence of Kentucky horse country, not only in appearance but also in productivity, not to mention in fabled history.

With Humphrey at the helm, the farm has produced high-caliber racehorses since 1979. Genuine Risk, winner of the 1980 Kentucky Derby, and Creme Fraiche, victor in the 1985 Belmont Stakes and six other Grade 1 races, are among the numerous prominent runners to be born and raised there.

Humphrey has been called one of the pillars of the American Turf for his achievements and service to racing. He served more than two decades on the board of Churchill Downs Inc. and is a director of the Keeneland Association. He also served four terms as a steward of The Jockey Club, held several senior positions with Breeders' Cup Ltd., and has been involved with other Thoroughbred industry organizations as well.

Many years ago, well prior to Humphrey's ascendance, Shawnee Farm was known as Leonatus Stock Farm. A colorful, now almost unimaginable, history is entwined in its roots, spanning afternoon racing, nighttime fox hunting, cock fighting, and gatherings of everyone from politicians to churchmen to racetrackers in events renown for revelry and bourbon imbibing.

The farm's owner, who named his property in honor of his 1883 Kentucky Derby winner Leonatus and who paid off the mortgage with the horse's winnings, was one of the truly colossal characters in Kentucky history.

More than 115 years ago, the Mercer County native also rose to be a staunch advocate for the sport when backing the steps that saved and elevated Kentucky racing. He has been called the father of Kentucky racing law.

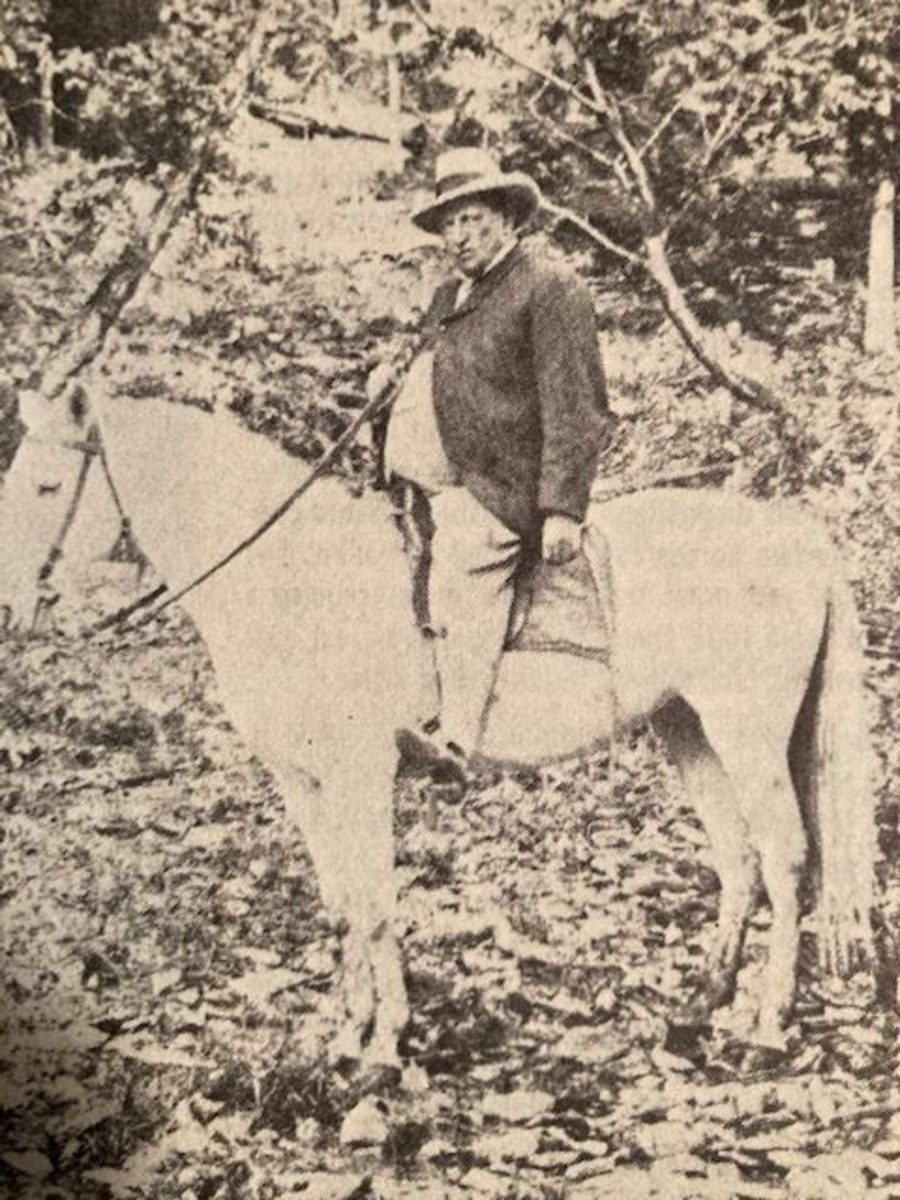

His name was John Pendleton Chinn, but nobody called him that. Better known as Colonel Jack Chinn, his charmed life, dynamic personality and sensational escapades on and off the racetrack thrust him into in the local and national spotlight for the decades bridging the 19th and 20th centuries.

“The first horse I ever had I stole to join Morgan,” Chinn once related, referring to his time as a Civil War soldier with Confederate General John Hunt Morgan, “but that was not the last horse I owned by any means.”

Indeed, Chinn went on to own and race many standout Thoroughbreds of yesteryear, including stakes winners such as Lissak, bred at Runnymede Stud; Ban Fox; Mary McGowan, and Josie M., to name only a few.

He also co-bred 1916 Kentucky Derby winner George Smith, who won his first seven races and 11 stakes over his career and was the famous namesake of the professional gambler better known as Pittsburg Phil. At age five, George Smith defeated two other Kentucky Derby winners, Omar Khayyam and Exterminator, in the Bowie Handicap while setting a Pimlico Race Course track record for 1 ½ miles.

Support our journalism

If you appreciate our work, you can support us by subscribing to our Patreon stream. Learn more.But Chinn's best horse was Leonatus, a son of prolific sire and multiple stakes winner Longfellow who he campaigned with his brother-in-law, George Morgan.

They bought the colt for $5,000 from breeder John Henry Miller after the youngster's second-place finish at Churchill Downs in his only start at two in 1882.

Leonatus won his seasonal debut at three, igniting a 10-race win streak, all stakes during a seven-week period from May 17 to July 5, for African-American trainer Raleigh Colston Sr.

Included in that dazzling streak was his Kentucky Derby win, achieved going 1 ½ miles over a heavy track amidst drizzling rain. Described as no more than 15.2 hands tall and heavily muscled, the colt was ridden by Canadian-born jockey Billy Donohue, who reportedly bet his life savings on the outcome.

In the winner's circle, Leonatus made himself even more noteworthy by noshing on the presentation roses that were customarily given to owners at that time, prior to the institution of the winner's blanket.

His $3,760 winner's share of the purse enabled Chinn to pay off what he owed on his Harrodsburg farm, with the colt adding even more to his accounts through victories in the Illinois Derby and the inaugural Latonia Derby; his owners reportedly turned down the then magnificent sum of $40,000 for the colt during his win streak.

While banking so much money, Leonatus became ensnared in a dispute after the Illinois Derby when Lawrence Martin pursued a legal claim against Chinn for a debt of $1,305 reportedly for “whisky, cigars and borrowed money.” Chinn had to post a bond for $3,000 to get the colt released.

Later honored as the 1883 champion 3-year-old male, as there were no such annual awards at the time, Leonatus holds the distinction of being the only horse to win the Kentucky Derby in just his third career start.

After Leonatus incurred a career-ending injury in a workout at age four, he was sold at auction in 1888 for $5,800 to Runnymede's Colonel Ezekiel Clay and Colonel Catesby Woodford. Chinn's son, Phil, walked Leonatus the 54 miles from Harrodsburg to Runnymede, in Paris, Ky., where he stood stud until his death from colic in 1898.

Leonatus was buried at Runnymede near the grave of imported multiple English stakes winner Billet, who coincidentally was America's leading sire of 1883.

Among the seven stakes winners Leonatus sired was Pink Coat, winner of the 1898 American Derby and St. Louis Derby, and Tillo, winner of the 1898 Suburban Handicap. Pink Coat went on to sire 1907 Kentucky Derby winner Pink Star.

Meanwhile, Chinn and Morgan acquired the Mercer County estate formerly known as Canehurst, built in 1824 by Colonel George Thompson, who had served as an aide to the Marquis de Lafayette in the Revolutionary War and was the commanding officer of Williamsburg, Virginia, in charge of 4,000 men. The property had been passed to his son and then his grandson, William Thompson.

Col. Thompson had owned up to 10,000 acres in the county, including the nearby Shawnee Springs estate. He imported holly trees from England for the grounds at Canehurst, and the entrance was guarded by sculpted bronze lions. Canehurst also was known for its deer park, a lush canebrake and fine-blooded horses.

Under Chinn, the new Leonatus Stock Farm was distinguished by a private racetrack built in 1885 by Harrodsburg resident Clark Currens, a nationally renowned fox hunter. Chinn himself was said to have hunted fox as well as an English squire.

Known for his broad-brimmed black felt hat, characteristic of the old-time Kentucky Colonel, with his vest adorned by a massive watch chain, Chinn was prominent in all aspects of Thoroughbred racing and in the politics of the state's Democratic Party, serving as a state senator in the early 1900s.

In that role, he was a visionary, authoring in 1906 the Chinn Act, which, in an era of anti-racing sentiment, brought structure, regulation and licensing to Kentucky racing for the first time and created the Kentucky Racing Commission. Chinn served as the commission's first chairman and also supported the adoption of the pari-mutuel system of wagering, which began in Kentucky in 1908.

Chinn perceived the effects of a multitude of racing days and rampant bookmaking as diminishing interest in the sport, which ultimately took a toll on the state's breeders. The commission was established requiring three breeders appointed by the governor to serve on the five-member panel.

“Colonel Jack Chinn, a widely known turfman, did so much to save the sport from annihilation,” the Louisville Courier-Journal asserted in a Sept. 17, 1922 piece titled Chinn Act Saves The State.

“Other states that had banned the sport have adopted the Kentucky law and transformed conditions.

“Colonel Chinn's foresight was not shared by other turfmen and he had to put up a stiff fight to bring about the reforms he set about to accomplish in the interest of the breeding interests.

“He told the opposition that either the 'bookmaker' or racing had to go, and that he intended that it should not be the latter if he could help it,” the article stated.

When Chinn died at age 72 in 1920, he was remembered as a big-hearted man and a big spender who suffered inevitable losses with valor.

He led a life of thrills, adventure, and accomplishment, and when he retired from racing horses, he earned acknowledgement as a top-notch starter at tracks around the country. He had also been a gambling hall operator, soldier, farmer, miner, fearless knife fighter, a teller of tales, and a connoisseur of chewing tobacco and Kentucky bourbon, often asserting that any other spirits were poison.

Chinn's adventures began early. He was just 14 years old when the Civil War began and he tried to enlist in the Confederate Army but was declared too young.

Left behind when his father and 17-year-old brother joined Morgan's band of raiders, Chinn stole a horse and ran away to join a scout detachment under guerilla fighter George Jesse. He later found Morgan before taking up with William Quantrill and becoming acquainted with outlaw Frank James, who later became a good friend and respected racetrack official.

With Morgan, Chinn eventually became separated from his father and brother, the latter being sent as a messenger to a house in Tennessee where Morgan was headquartered in April 1864.

A bloody skirmish at that location led to his brother being captured and Morgan killed. Although later freed in a prisoner exchange in Atlanta, the brother was killed in a cavalry fight six months later in Saltville, Va.

Chinn and his father recovered their beloved relative's body on the battlefield, his father placing the remains over his saddle in front of him and riding to a churchyard to bury him. Legend has it that his brother's horse found his way home to Harrodsburg from Virginia, more than 250 miles away.

One of the many skills Chinn learned as a soldier was the use of a knife, and he fashioned one of his own, said to be an improvement on the old Bowie blade with spring action. He kept his knife handy in the right rear pocket of his trousers.

In the post-Civil War era in Kentucky, where violence was part of everyday life, his knife was a useful weapon, and he survived many confrontations due to his skill in handling it.

“The revolver is too common, too vulgar a weapon for a gallant gentleman like Colonel Jack Chinn,” said a writer in a 1903 Pittsburg Dispatch story.

Chinn had a non-lethal run-in at the old Latonia racetrack in Northern Kentucky, during which he twice stabbed an assailant. Another time, he was shot in the mouth by a policeman—at the behest of a criminal gang—when at the races in St. Louis, where he was a starter, and fell clutching the knife in his hand. The policeman committed suicide when told Chinn would recover.

In some accounts, Chinn has been ranked among American's best knife fighters, all Kentuckians, with only frontiersman Jim Bowie, abolitionist Cassius Clay, and jurist and politician David Terry described as more skillful.

While perhaps best known for brandishing knives, Chinn also carried guns, and during a saloon brawl in Harrodsburg in 1905, he was arrested, jailed, and convicted for carrying a concealed firearm.

Some metropolitan newspapers found Chinn made for good copy and stylized him as a hero of mythical proportions, much like Paul Bunyan or John Henry. His exploits were at times sensationalized, and occasionally he was portrayed as a madcap ruffian and a “fighting terror,” according to a 1934 report in the Lexington Leader.

“Go ahead, sonny. Print anything you like about me. I can stand it if the public can,” Chinn told a reporter.

Perhaps the only time he objected to depictions of him was when the maker of Doan's Kidney Pills used a likeness of his image and a fake testimonial to promote the medication. He sued and won several thousand dollars.

Although noted for his flamboyance, Chinn experienced another dark chapter in his life aside from his time as a soldier.

Considered a close friend, champion, and bodyguard of controversial Kentucky Governor-elect William Goebel, Chinn was walking with him when Goebel was shot by a sniper outside the Old State Capitol in Frankfort in 1900.

Chinn was one of the state's main witnesses in the trials of a number of people implicated, but to this day the murder is unsolved, and Goebel remains the only American governor to be assassinated while in office.

From that time, Chinn was actively involved in politics.

When Nebraska orator and lawyer William Jennings Bryan ran for the U.S. presidency in 1900, his second of three unsuccessful campaigns, Chinn and some of his associates stumped for him in Kentucky.

Racing and racetrack life were constant threads throughout Chinn's life; he grew up with his father and grandfather both racing horses in the years prior to the Civil War. Chinn raised four sons with his wife, Ruth Morgan Chinn, a distant relative of the Confederate raider, and introduced them to the sport as well.

His son Phil became one of the most respected Kentucky horsemen of his era while operating Himyar Stud near Lexington. Another son, Christopher, named after Chinn's late brother and nicknamed 'Kit', followed in his footsteps by working as a racetrack starter.

When the original Canehurst home burned in 1888, the Chinns moved into a two-room cottage and over time expanded it to 14 rooms, using the space not only for family but for several Confederate veterans they supported through charity. The veterans kept the hounds in prime hunting condition and tended to the game chickens.

Known as the “Little Chinn House,” the house still stands at Shawnee Farm.

As he was growing older, Chinn sold Leonatus Stock Farm in 1912 and moved to nearby Mundys Landing in Woodford County, where he operated a mine along the Kentucky River. The calcite extracted was shipped to New York and used to produce optical glass for binoculars and periscopes employed during World War I.

When Humphrey's aunt, horsewoman Pansy Poe, was seeking to buy a Kentucky farm, she found the acreage that had been Leonatus Stock Farm as an ideal place to hunt her fox hounds, retire her polo ponies, and raise Thoroughbreds, and she bought the property in 1938. Humphrey acquired the farm from her estate when she passed away in 1979.

Long before then, in 1955, Poe had made her own history as the first woman elected to serve on Keeneland's board of directors. The esteem in which she was held is yet another component of the service and accomplishment in the Thoroughbred industry that is today a hallmark of her nephew and his Shawnee Farm, as well their fabled forerunners.

The post Kentucky Farm Time Capsule: A Kentucky Rascal, Father Of State’s Racing Law, Was Former Owner Of Shawnee Farm Property appeared first on Horse Racing News | Paulick Report.