In the week and a half since the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority released its 2023 cost assessments to racing states, we've heard a lot about sticker shock from officials and horsemen – and a great deal of confusion.

You can read the Authority's press release about the 2023 budget here.

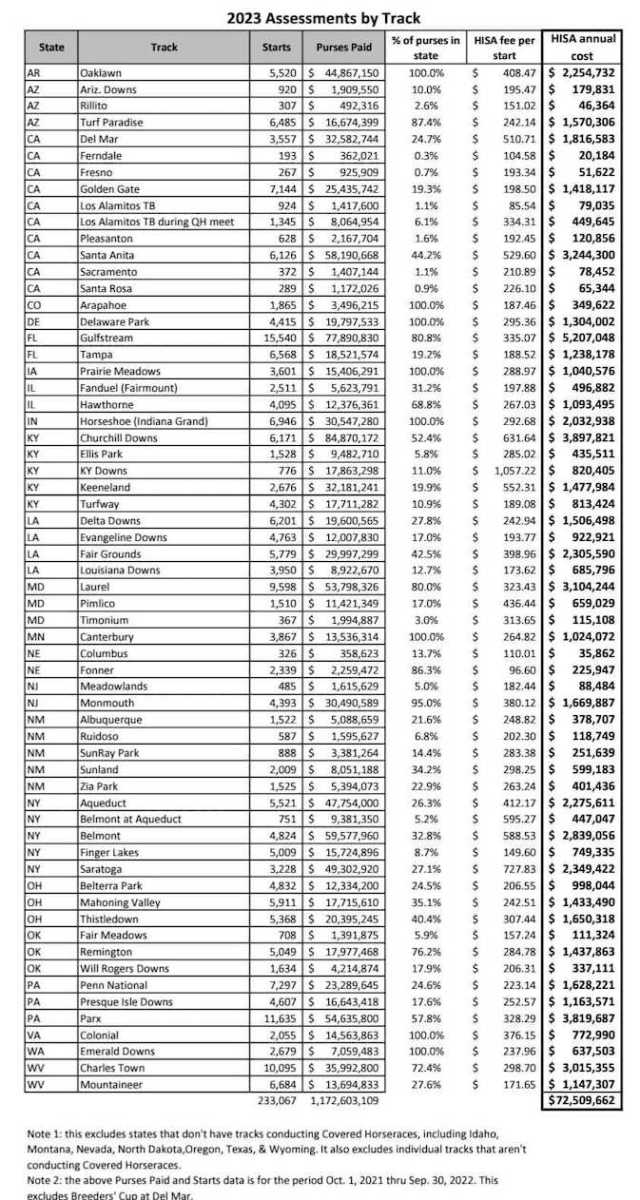

The overall budget for Authority operations in 2023 is projected to be just over $72 million. That includes both the cost of the track safety program that was launched this year, in addition to the anti-doping and medication control portion, which is slated to start Jan. 1, 2023. Per the federal act signed into law by former President Donald Trump, the medication portion is to be administered via a separate but related agency called the Horseracing Integrity and Welfare Unit (HIWU).

When HIWU takes over, the Authority will set medication rules and HIWU and the Authority will be responsible for collecting post-race and out-of-competition samples, having those samples tested, reporting positive results, issuing sanctions, and arbitrating cases on drug rule violations. Previously, these responsibilities have been paid for by the state in most cases, with the racetracks or horsemen's groups sometimes kicking in for the expense of a laboratory contract.

What startled many regulators last week was a document that showed an estimated per-start cost of the program, broken down by racetrack. The per-start costs varied widely and ranged from $85.54 (Los Alamitos' Thoroughbred meet) to as high as $1,057.22 (Kentucky Downs). Those costs aren't yet a certainty for some or all of those race meets, however.

Here's why.

The projected bills dispersed last week went to state racing commissions, in much the same way as they did this summer ahead of the implementation of the racetrack safety program on July 1. There are a few different ways these bills may be paid. The simplest way is for a state commission to decide they will pay the entire cost themselves. Only a handful of states did this with the track safety portion and it's not yet known if the same states will shoulder their full cost of this larger bill.

Another option is that a state may decide it won't be responsible for paying the fees, in which case the expense defaults to the racetracks. That is where the per-start fee schedule would kick in – if tracks become responsible for collecting the money. The per-start fees in the table above are based upon a similar formula as the Authority used to decide how much of the budget each state is responsible for paying. This is determined by the number of starts at a state's racetracks, weighted in combination with the purses it pays out. It's designed to make states that have frequent, more lucrative races (like Kentucky or California) pay more than states with infrequent racing (like Colorado), or year-round circuits that don't generate much purse money (like West Virginia).

Become a Paulick Report Insider!

Want to support our journalism while accessing bonus behind-the-scenes content, Q&As, and more? Subscribe to our Patreon stream.(It's important to note that formula may change; it's one of the aspects of the federal law that states are challenging in federal court. A judge in one of the civil cases already agreed with the plaintiffs that the formula shouldn't be weighted by purses and should be based on start volume only. Since that litigation isn't yet finalized, the Authority made its budget based on the weighted formula, but if it is forced to adjust, it will be states like West Virginia and Louisiana – two of the states suing the Authority – that will have to pay more.)

There's also a third option. The Authority has offered each state the opportunity for a series of credits if the state allows its existing human resources to be used by the Authority. For example, commission-employed veterinarians or sample collection personnel who are currently collecting drug and urine for the state could next year remain employed by the state, doing their same jobs, but work under the direction of HIWU and send those samples off to HIWU's contracted lab. The Authority is willing to offer the state a credit for the costs it would take for HIWU to hire these people, because now it won't face that burden or expense. That credit can go against the bill handed to the state. In many cases, HIWU would incur a higher cost when hiring someone new as a private agency than what a state likely pays an existing employee.

“States can get credits for collectors for both post-race and out of competition testing, for investigators, for stewards performing investigations, for laboratory testing either as a credit if the state continues to pay or as budget relief if HISA pays directly,” said Lisa Lazarus, CEO of the Authority. “They also will have significant budget relief on enforcement and legal costs since they will not be responsible for prosecuting anti-doping & medication control violations or defending any lawsuits related to anti-doping or medication control events.”

A state could decide it wants to pass the bill onto the racetracks but also that it's going to provide assistance to the Authority that will get credits applied to the bill first, so the amount owed by the tracks is smaller. That would mean those per-start fees could be lower – maybe a lot lower.

Lazarus told the Paulick Report it remains to be seen how states are going to handle these three choices. In some cases, the states fighting HISA in court may not be interested in cooperating at all (and could face sanctions if they don't). In other cases, states have raised questions about whether they legally can retain employees who will be answering to another agency.

It's also not easy to tell states how big or small the difference is between the Authority's bill and the costs they're already paying for the same services.

“The difficulty is multi-faceted,” said Lazarus. “In many states, costs are commingled with other breeds and across other government services both in and outside of horseracing. In some states, there is a reluctance to share the information because of past underinvestment in safety and integrity.”

Big picture though, Lazarus believes the anti-doping and medication control portion doesn't represent a hugely different national figure than what's being spent now on drug testing.

“If all the states cooperate with HISA and are able to direct existing anti-doping and medication control funding to HISA, the incremental cost is between $20-25 million,” she said. “This difference between what is being spent now and what is budgeted reflects a history of underinvestment in safety and integrity and the reality of what is necessary to have national, harmonized and robust Anti-Doping & Medication Control and Racetrack Safety Programs across the U.S.

“What we do know is that in two surveys conducted in 2014 and again in 2019 by independent consulting firms, it was estimated that Thoroughbred lab costs are somewhere between $13.2 and $13.8 million. This was several years ago and HISA's budget for lab costs in 2023 is $18.7 million, which is approximately a $5 million difference and represents the necessary upgrades to deliver the ADMC Program required by the Act as well as inflation costs.”

So, what's next?

Most states will have to come up with a response to the Authority in the next month or so about how it intends to pay its bill. As the start of 2023 is fast-approaching, none of them have a terribly long time to make up their minds. If you're an owner or trainer wondering what your state or racetrack plans to do with their bill, you may consider looking up the date of your next racing commission meeting and being in attendance.

The post HISA Has Released A $72 Million 2023 Budget; What Happens Now? appeared first on Horse Racing News | Paulick Report.