Ten years have passed since the New York Task Force on Racehorse Health and Safety issued its report and recommendations in response to a cluster of 21 racing fatalities over a 15-week period from Nov. 30, 2011, through March 18, 2012.

The task force, formed at the urging of then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo, was comprised of attorney Alan Foreman, chairman and CEO of the Thoroughbred Horsemen's Association; retired Hall of Fame jockey Jerry Bailey; Dr. Mary Scollay, then equine medical director of the Kentucky Horse Racing Commission and currently chief of science for the Horseracing Integrity & Welfare Unit; and Dr. Scott Palmer, an equine surgeon and former president of the American Association of Equine Practitioners. Palmer was named chairman of the task force.

The task force's mission was to investigate the cause or causes of death in the 21 fatalities; examine the racing surface at Aqueduct; review policies relating to public disclosures, necropsies, track conditions and pre-race examinations; and examine rules and practices concerning claiming procedures, veterinary procedures, and equine drug use.

One of the key recommendations of the task force was the appointment of an equine medical director for the New York State Gaming Commission, a position that Palmer accepted in January 2014.

Palmer and Foreman were also part of a team that developed the Mid-Atlantic Strategic Plan to Reduce Equine Fatalities, a 2019 paper that developed best practices on a variety of safety-related issues for the Mid-Atlantic region.

So, 10 years after the task force report and three years after the Mid-Atlantic strategic plan, have fatal injuries been reduced at Aqueduct and the other New York Racing Association tracks, Belmont Park and Saratoga?

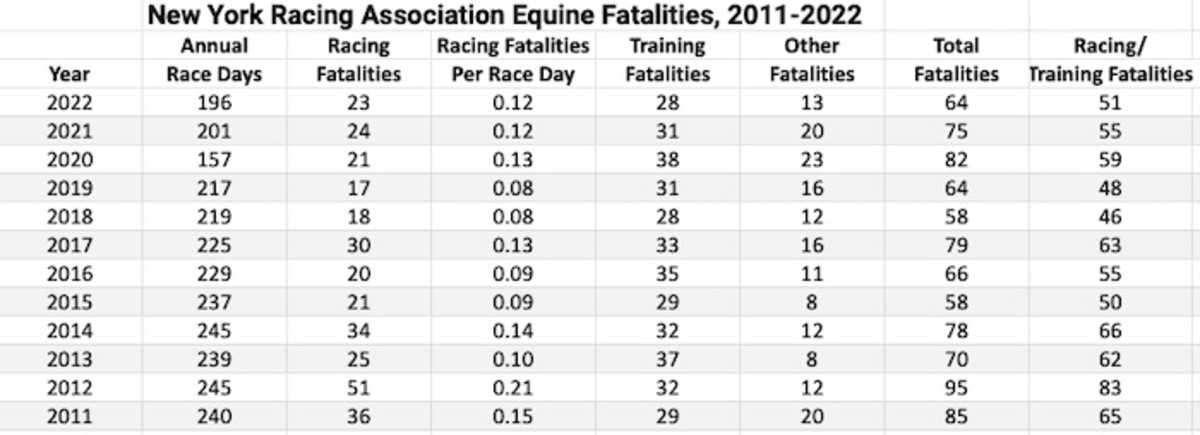

Based on statistics compiled by the Paulick Report from the NYSGC's online database, fatal racing injuries are down significantly from 2012, when 51 horses died. In 2022, 23 horses were listed as having died from racing, either as a result of musculoskeletal injuries or sudden death. That's a decline of 55 percent. Over the same span, the number of racing days has declined by 20 percent. In 2012, there were 0.21 fatalities per race day (roughly one every five days). In 2022, there were 0.12 fatalities per race day (one every eight days).

Training fatalities or “other” deaths (colic and laminitis being the leading causes) have not declined nearly as much as racing fatalities. Training deaths actually increased from 32 to 37 the year after the task force recommendations and there were 28 in 2022, just a 13 percent decline from 2012. Training fatalities saw a 10-year high with 38 deaths in 2020, the year the coronavirus pandemic disrupted racing and training. The number of horses that died from other causes has increased in recent years compared to 2012, also hitting a 10-year high of 23 in 2020.

To review the progress made at New York Racing Association tracks over the last 10 years and the challenges that remain, a number of questions were submitted to Palmer, New York's equine medical director. Following are those questions and answers:

Since 2012, when the Task Force was formed to address the spike in fatalities at Aqueduct, racing and training fatalities (not including “other” or “unknown” deaths) at NYRA tracks are down almost 40%. What do you think are the biggest factors that have helped lead to the reduction?

Dr. Scott Palmer: There are many factors that impact equine health and safety. At NYRA tracks, the reduction of equine fatalities can be attributed in part to implementation of a comprehensive risk management program and the recommendations of the New York Task Force on Racehorse Health and Safety. Some specific factors include but are not limited to:

- New York's appointment of an Equine Medical Director

- Stricter voided claim rules

- Claiming purse-to-price restrictions

- Prohibition of analgesic medications and joint injections in horses within a timeframe leading up to a race

- Strict regulation of thyroid hormone medicine in horses

- Enhanced protocols for pre-race inspections of horses

- Required continuing education for all trainers and assistant trainers

- Real-time race surface monitoring and maintenance procedures

On the other hand, comparing 2022 to 2015 and 2016, the statistics on racing and training fatalities have not improved. When you consider the reduction in the number of racing days the last several years, the numbers look slightly worse. Does this suggest there's no more room for improvement?

Absolutely not. There is ALWAYS room for improvement when it comes to equine health and safety. New York's goal is zero fatalities.

Risk management is an ongoing, iterative process that includes:

- Performing a risk assessment to identify risk factors.

- Implementing interventions to address those risk factors

- Monitoring metrics to determine if interventions are successful

- Modifying current interventions or implement new interventions as required to address changes in risk.

With that said, the premise of your question is inaccurate (which is discussed later). Over the past five years, there has been a relative increase in equine training fatalities in contrast to a decrease in equine racing deaths.

One factor is that, by its very nature, training is not regulated in the same manner as racing.

There is a difference in the degree of veterinary scrutiny of horses immediately prior to a race compared with that provided to horses that are training.

For horses that are racing:

- On the day of a race, a pre-race inspection is performed in the morning. Based upon the results of this inspection, horses of concern to the regulatory veterinarian are not allowed to race.

- All horses are visually inspected by regulatory veterinarians as they enter and walk the paddock, during the post parade, and while warming up before they are loaded into the starting gate.

Similar scrutiny of horses before and during training is undertaken. However, I am encouraged by efforts to further involve attending veterinarians in evaluating horses prior to training. We are considering a requirement that an attending veterinarian attest to the suitability of a horse to train. This cannot, however, just be a paper requirement. To be effective it would require an attending veterinarian to undertake a review.

We are likewise enthused by biometric sensor devices being placed on horses during training as a scalable means to identify Thoroughbred racehorses with subclinical lameness or gait abnormalities. Such lameness is usually impossible to diagnose by veterinary inspection alone. I believe the increased use of this technology can lead to a significant reduction of training fatalities.

In 2019, Santa Anita in California had highly publicized problems with fatal injuries similar to Aqueduct in 2012. Has New York taken anything from the safety protocols they've put in place in California that have successfully reduced the racing and training fatalities?

Yes. California has made a conscientious effort to create a culture of safety at Santa Anita Park. Increased veterinary scrutiny of horses and collaboration between attending and regulatory veterinarians has been critical to their process. Additionally, Santa Anita installed advanced imaging equipment (PET Scan) to help identify horses with pre-existing musculoskeletal lesions that are not evident on routine radiographs. It might be worth examining the interventions implemented due to PET scan availability.

What procedures do you or other regulatory veterinarians undertake when you receive a necropsy report? Does someone meet with the responsible trainer?

Multiple veterinarians review necropsy reports and communicate significant findings with the responsible trainer. The open line of communication between veterinarians and trainers leads to implementation of best practices to protect horses. This process, along with the racing risk management program developed in New York and employed by all Thoroughbred tracks in the Mid-Atlantic region, was incorporated into the HISA safety regulations that are now in place across the U.S.

What types of investigations are done when a horse suffers a sudden death? For example, Herecomesangelina collapsed and died on March 14 and the NYSGC data base note says the investigation is ongoing. What steps are taken during the investigation?

Please see attached protocol from the Task Force Report. This protocol is in effect.

Have you learned anything during those investigations?

Yes. The Commission and/or NYRA searches an applicable trainer's barn to determine if any drugs known to produce cardiac arrhythmia are present. We interview trainers and attending veterinarians regarding medical treatments that may have been administered and consider the clinical history of the horse. Additionally, the necropsy examination for cases of exercise-associated sudden death in racehorses includes a thorough microscopic examination of the heart muscle and conduction pathways in the heart.

The majority of the necropsy examinations of exercise-associated sudden death cases have found no physical abnormalities. However, in some cases we have found evidence of cardiac muscle necrosis, chronic inflammation of the cardiac muscle and one case of congenital abnormality. Similar to findings in human athletes, these horses likely experienced an electrical conduction abnormality in the heart that leaves no trace in the body after death.

Herecomesangelina is one of 10 horses in the barn of Rudy Rodriguez that died in 2021-22, more than any other trainer. What can be done in cases where one trainer has so many horses die?

Based on available information, it's evident that Mr. Rodriguez' stable consists primarily of horses obtained via claiming races. As outlined in the Task Force Report, claiming horses are inherently at increased risk for injury and death.

Our Stewards and I regularly speak directly with trainers – including Mr. Rodriguez – about the increased risk for injury in horses that race in claiming races and encourage them to use increased vigilance when training these horses.

One challenge trainers face is that there is usually no overt clinical sign of lameness in horses that experience exercise-associated musculoskeletal fatalities. This makes it challenging to identify horses at increased risk for injury based upon physical inspection alone.

Use of biometric sensors during training and racing will help to identify horses at risk and prevent musculoskeletal injury, particularly in horses that race in higher risk race categories, such as claiming races.

Do you feel any of the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority regulations put into place July 1 have made a difference?

Yes. The HISA whip rule has changed the way that jockeys use the whip during a race. However, with regard to HISA's impact on the number of equine injuries and/or fatalities, it is too soon to tell. Equine fatalities are now so few in number that making an objective comparison of the rate of injuries during a short period of time is challenging.

I am encouraged by HISA's reporting requirement for tracking non-fatal musculoskeletal injuries and look forward to seeing the data, as that will be an important factor in measuring the general soundness of our racing population.

HISA's Anti-Doping and Medication Control regulations have not been approved yet, though you've had time to review them. If the Federal Trade Commission approves regulations similar to those submitted last year, what will be the biggest changes that might reduce the number of fatal injuries or sudden deaths?

As stated previously, there are many factors at play in equine health and safety. New York's present regulations regarding medications are very similar to those in the HISA ADMC regulations. Therefore, I do not anticipate that implementation of the HISA ADMC regulations will have an immediate, dramatic impact on the number of injuries or sudden deaths. However, I do look forward to HISA's required contemporary medication reporting by attending veterinarians, which is part of the existing HISA safety regulations. This required documentation of medication use is likely to help reduce the use of pain control medication in close proximity to the race, in turn reducing the risk for equine musculoskeletal injuries.

Editor's Note: Palmer suggested the data compiled by the Paulick Report would be more accurate had total starts been used rather than race days, then shared the analysis he uses. He also volunteered that fatalities have declined at New York's other Thoroughbred track, Finger Lakes, which is not operated by NYRA.

Palmer: I question the use of “race day” as a metric for the measurement of equine injuries.

The metric used by the Commission's Equine Injury Database of “fatalities per start” is a more accurate measure of risk as it takes into account the variability of the number of starters in each race, which is not considered when using a “race day” metric. The use of starts holds constant the differences that occur because of changes to a racing schedule and is therefore a more consistent year-over-year metric.

Below are the metrics I use to monitor the prevalence of racing, training, and other fatalities:

| NYRA Fatality Incidence Rates – 2017-2021 | |||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

| Racing Fatalities | 30 | 19 | 17 | 21 | 24 |

| Number of Starts | 16241 | 14987 | 14842 | 11817 | 14628 |

| Racing Fatalities/1000 Starts | 1.85 | 1.27 | 1.15 | 1.78 | 1.64 |

| Training Fatalities | 33 | 27 | 32 | 40 | 31 |

| Number of OTW | 49878 | 48024 | 45962 | 43627 | 46724 |

| Training Fatalities/1000 OTW | 0.66 | 0.56 | 0.7 | 0.92 | 0.66 |

| Other Fatalities | 16 | 12 | 17 | 21 | 21 |

| Number of Horse-Days | 177876 | 167659 | 166744 | 142161 | 160949 |

| Other Fatalities/1000 Horse Days | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.13 |

The Commission classifies fatalities using a different standard than the Equine Injury Database in that the EID classifies only those exercise-related fatalities that occur within 72 hours of the incident, while the Commission classifies fatalities as exercise-related regardless of the time interval after which the death, typically via euthanasia, actually occurs.

Not asked but important to the discussion: Finger Lakes Racetrack has seen a significant reduction in racing fatalities. In 2011, there were 31 racing fatalities (2.9 per 1000 starts) compared to 4 (0.8 per 1000 starts) in the past year. This is relevant because the changes implemented by NYRA after the task force report were also implemented at Finger Lakes. Additionally, the same changes have been implemented at Thoroughbred tracks in the Mid-Atlantic states (14 tracks).

The post 10 Years After Task Force Report On Aqueduct Fatalities, New York Equine Medical Director Reflects On Progress, Challenges appeared first on Horse Racing News | Paulick Report.